In-Sights

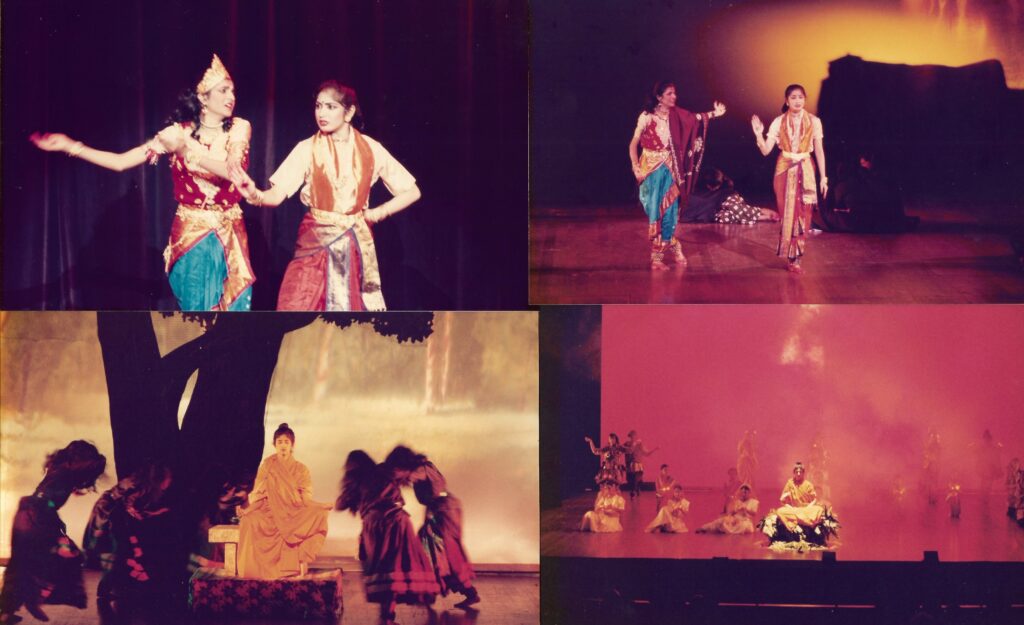

Vidhya Venkat shares her observations on Apsaras Arts performance space Avai, and in India, also performances by visiting international artistes and Singapore based artistes. Gibran “I love you when you bow in your mosque, kneel in your temple, pray in your church. For you and I are sons of one religion and it is the spirit “ – Khalil Gibran, The Prophet We were treated to an evening of wisdom from Khalil Gibran. While we have been used to dance and vocal concerts in Avai, this was a very good break from that. Excerpts from The Prophet were narrated by Ramesh Panicker who conceptualised this show. He was accompanied by Azrin Abdullah on the Arabic Oud, a lute-like stringed instrument. The setting was reminiscent of an Arabic tent and Gibran’s works were shared in the way of storytelling. Three days fully sold out and we were all treated to some inspiring words from Khalil Gibran – looking forward to more of such programs. The performance was the brainchild of Audrey Perera and produced by Passion Purpose and Apsaras Arts. Balinese Classical Dance Performance We watched a beautiful performance of Balinese dance by Prof I Wayan Dibia and Geok Ensemble Dancers on July 16, 2022, at Avai. Aravinth Kumarasamy Artistic Director mentioned in his introductory speech that the Natya Sastra is the root and then we have the many beautiful manifestations of this text and that evening we saw one of the most beautiful manifestations. As Prof Dibia detailed, there are so many common elements in these dance forms. We saw Aramandi, Chowk, Tribhanga and also an amazing display of the Sthayi Bhava of Vira rasa, something which we don’t come across so much. The eye movements were almost hypnotising- diagonal, side and down. And finally, Prof Dibia ended the show with his solo – The masked man. As he rightly said, the challenge is to bring the mask alive and I think he did just that. Costumes were so detailed and so beautiful, each one of them. When asked for advice to budding dancers, Prof Dibia said, “Learn physical movements first and then learn how to use energy on them. You then move on to the norms and ethics of the dance form, spiritual contemplation and philosophy of the dance. Dancing is about love and when you dance with love, it comes from the heart.” I came away with this message in my mind, a thought which must echo in every dancer’s heart. A huge world of learning and research opened up for me. A befitting first anniversary for Avai ! And awaiting many more. Aaradhana for Nadopasana concert series remembering S Sathyalingam. Hindustani performance of Aaradhana was presented at AVAI at Apsaras Arts featuring Shibani Roy (vocals) and Debashis Adikari (harmonium) from SIFAS and Lalitkumar Ganesh (tabla) from TFA, Singapore. Shibani performed a good selection of ragas and very delightful ghazal. Sparsh – The Touch A Kathak performance by Amprapali Bhandari as part of Darshana series on 2nd July at Avai. Amprapali started the evening with a traditional choreography in Teental. This was in the traditional Jaipur Gharana that blends abhinaya with nritta. She covered the veer rasa, bhakti rasa and shringara rasa. We then journeyed into the monsoon season. The sky is changing colouras though being robbed of lifeAs thunder rolls, lightning strikesThe sky splits in halfDrop after dropThe rain arrives The above verse from Ritusamhara started the next piece. The human being is as complex and multilayered as the monsoon. Rather than only focussing on the colours and rainbows, we must learn to accept all parts of ourselves. This piece which was choreographed by Amrapali herself talked about the multi dimensions of human emotions – passion, anger, love and surrender. She had approached the choreography in a contemporary style with just a sarangi playing in the background. It was very refreshing and new. AMARA: India Tour August 2022 Apsaras Arts Dance Company presented the world premiere of the live performance of AMARA, Dancing the Stories of Banteay Srei in India for the celebration of Nirthyodaya’s 80th anniversary and for India at 75, at the Kalakshetra Foundation. Banteay Srei is unique among Cambodia’s famous sacred buildings. It stands out from other ancient Angkorian temples with its petite size, the pink hue of the hard, red sandstone from which it is made, and the intricacy of its exquisitely sculpted wall relief carvings of motifs, figures and scenes from the Hindu Mahabharata and Ramayana epics. Built by Khmer courtiers in the 10th century, Banteay Srei was originally named Tribhuvanamaheshwara, and its surrounding town named Isvarapura, both in dedication to Lord Shiva, though the temple venerates both the gods Shiva and Vishnu. Later on, it was dubbed Banteay Srei or Citadel of Women in Khmer, perhaps in tribute to the plethora of enchanting female devatas (deities) adorning the temple’s walls as well as the life-sized sculptures of yogini (sacred women) found within its compound. See these ancient figures and scenes from the Hindu epics come to life and listen as the yoginis unravel mystical stories of the sacred temple in this exhilarating dance production. AMARA is by Singapore’s Apsaras Arts Dance Company, established in 1977, by Shri S Sathyalingam and Smt Neila Sathyalingam, Alumni and former faculty at Kalakshetra Foundation, India. Apsaras Arts is the inaugural recipient of Stewards of Intangible Culture and Heritage award by Singapore’s National Heritage Board in 2020. The dance company has been led by award winning artistic director Aravinth Kumarasamy since 2005. AMARA at Nrithyodaya Honoured to have been presented at the three-day festival celebrating Nrithyodaya’s 80th anniversary at the Narada Gana Sabha, Chennai. The festival was curated and presented by dance doyenne Dr Padma Subrahmanyam. AMARA performance was presided by N Murali, the president of Madras Music Academy, and leading dance legends Priyadarsini Govind and Shobhana. AMARA at Kalakshetra Foundation Blessed to have had legendary dance gurus, VP Dhananjayan, Shantha Dananjayan, Dr Padma Subrahmaniyam, Lakshmi Viswanathan and Kalakshetra Director Revathi Ramachandran who were present to

Interview

Passion, perseverance, gratitude and a sense of continuity mark Kuchipudi dancer-choreographer-teacher-curator, Rajyasri’s career in dance; she traces her journey as a student of dance, her life in Singapore, and how she continues to engage with dance, based now in Bangalore You were in Chennai recently for an Apsara Arts show. How did it feel to be in Chennai? In a way, this is where it all began for you right? Visiting Chennai is always nostalgic. This is where I spent my childhood and adolescent years. My parents and in-laws lived in Chennai as well for many years after I left, so returning to Chennai always felt like home in some sense. This city holds many fond experiences and memories that are significant to me such as my education and of course, dancing, which I started and grew to love while growing up there. In the land of Bharatanatyam, what drew you to Kuchipudi? Talk to us about your early days of training. My mother was very fond of the arts and wanted her daughters to experience a variety of their forms. Although I started off learning to play the veena at first, my heart was not entirely in it and my fascination was always with Indian classical dance. When my mother realized this, she eventually had me pursue this passion by enrolling me in dance classes. This was when my experience with dance first started. Although we lived in Chennai, we hailed from Andhra Pradesh, so it just felt natural that I wanted to learn Kuchipudi, the dance form which originated from our home state of Andhra. Dr Sri Vempati Chinna Satyam, fondly known as Master Garu, was the pioneer and founder of Kuchipudi in Chennai, and through his dedication of spreading this dance form, he established the well-known Kuchipudi Art Academy in T Nagar in Chennai, which is the dance school I attended. Tell us about your guru and what are some of the key learnings from him in terms of dance and life? Kuchipudi was mainly conducted in the format of a dance-drama, and only male dancers performed all the characters. Master Garu was the one who encouraged female dancers in Chennai and was dedicated to making Kuchipudi inclusive to all dancers. He would never force or chase his students to pay their dance fees, as he strongly believed that art should be taught and spread, but never sold. His devotion to the arts resulted in his achievements of numerous titles and awards such as the Raja Lakshmi Award of Madras, the Kalaprapoorna from the Andhra University, the Kalaimamani award given by the Government of Tamil Nadu, and the National Award from the Central Sangeet Natak Akademi in New Delhi, to name a few. His popularity grew within the United States as well, where he was given the Golden Key to the cities of Miami and Atlanta. His discipline and commitment were just some of the qualities that most of us learned and embodied in our daily lives. From his humbleness, to his compassion, his kindness to his warmth, Master and his wife always ensured that his students were cared for and we respected each other like family. I believe these are the traits which greatly influenced us while under his mentorship, and are the same characteristics I continue to employ in all areas of my daily life. What was the dance community in Chennai like when you were growing up? Bharatanatyam was the only well-known art form while I was growing up. Master, along with his senior students, had to struggle initially in introducing Kuchipudi to the dance field. Their hard work paid off when the Kuchipudi Art Academy produced over 12 large-scale performances, and each production received great reviews. Senior students like Shobha Naidu, Manju Bhargavi, Bala and Anupama were some of the senior students who dedicated themselves to helping spread and develop Kuchipudi in and around Chennai. Within two years of learning under Master, some of my classmates like Madhavapeda Murthy, Satyapriya and I got the chance to perform in a few of Master’s productions and also travel with him and his senior students for solo performances. However, while studying full-time in college, it was not possible for me to completely dedicate myself to dance. I did, however, participate in several inter-college art competitions and together with Jayanthi Subramaniam and Roja Kannan, we won several competitions for our college. Through the growth of the Kuchipudi Art Academy, and its numerous productions, Master was looked upon as a dance guru and choreographer par excellence, and a legend in this art form especially after his award-winning achievements. What took you to Singapore and how did you feel when you arrived? When I got married, my husband Murali was already working in Singapore. It was my maiden international trip and I was very nervous. Leaving family, friends, and dancing behind and moving to a totally new environment was overwhelming at first. However, with the love and support of my husband, in-laws and the friends we made from our cultural communities, I settled in quickly. You are responsible for taking Kuchipudi and popularizing it in Singapore. How did it all begin? Before I shifted to Singapore, my guru had attended a dance program in Singapore, where he met with several organizers from the dance industry. He spoke to them about me and mentioned that I would be settling in Singapore and was capable of teaching Kuchipudi. When I moved to Singapore in June 1981, I wanted to pursue my studies further before taking a full-time job, but I had to wait for my Permanent Residence status first. So, in the meantime, I met Mr and Mrs Bhaskar at a performance and they offered me a place to start my classes. Within a couple of months of my arrival in Singapore, I started my Sunday morning Kuchipudi dance classes. I am grateful to Aunty and Uncle Bhaskar for giving me the foundation to start, build and spread the art

POINT OF VIEW

As a huge loyalist of the world of social media, Akhila Krishmamurthy, Founder of Aalaap, shares some thoughts on the good, bad and the ugly and why dabbling with it, is a story of to each, its own Over the last two-and-a-half-years or so, around the time we all burrowed ourselves into the security and comfort of our homes, while an epidemic gripped the world and rattled our senses, artistes and arts organisations from across the world, turned to social media as a means of refuge, a source of succour. Through the years of the lockdown, personal social media handles became platforms for artistes to share, showcase and amplify their work with a larger universe. Some artistes had already built a brand identity on these platforms; while some others started afresh recognizing its power and potential for networking and as a means to build for oneself a brand of one’s own. A handful of artistes consciously opted to stay out of it, away from it, choosing to neither share nor express their points of view on the arts, or things off it, on these platforms. Over several conversations with several artistes – those who used social media extensively, moderately or chose not to engage with it at all – I take home many mixed perspectives and recognize that like most things that are inherently personal, social media too is a matter of choice. And like all the best things in life that must not be consumed in excess, social media too, we can conclude is an indulgence where it is crucial to apply the principles of moderation and caution. Thanks to Artificial Intelligence, my feed was exclusively dancers and all things dance. And while it was fantastic to discover young and new artistes from across the globe, I also grappled with a sense of angst as I wondered about the principles of good content, and how the ephemeral nature of social media was also crippling our brains and minds, shunting our focus, overloading our senses and making us inherently fragmented and distractible as human beings. I realized the first thing I would do, when yet another dance video came my way was to check its duration; and I realized that on some days, even watching a two-minute video seemed like a Herculean task; the mind had already moved on and was restless to check the next reel, the next post, the next new dancer sharing her dance or the old dancer giving her dance a new spin! But before you begin to question me about my value judgements, let me admit that I, as an individual and in my capacity as the founder of Aalaap, am hooked onto social media. It is where we have shared our joys and fears, our angst and anxieties, our growth and journey, our events and initiatives. As a performing arts magazine that was born in 2014, social media became a natural extension for us to curate content that we believe is honest, authentic, objective, inclusive, diverse and truly a celebration of the dance community, at large. And we have been on this bandwagon well before the pandemic arrived; we didn’t panic when we had to transition into this medium because even before that, we have been busy on these platforms, bringing people together, amplifying their stories and ours and doing our bit to create a culture of happiness and harmony amongst the community. But social media, we realise, one day after another, is a beast of its own and one that we need to negotiate our way through; it’s almost like a lover who will play hard to get (followers in this case) if you don’t water it consistently or allow it some outdoor so the sun shines its light for growth. Social media is a constant work-in-progress but also one that you need to think through in terms of the very principles of journalism – what, where, when, why, who, how! Everyday, we look through our content through these parameters and attempt to share content that truly elevates and brings joy. With the world now opening up, some artistes who were insanely active on social media have abandoned it for the real world; some others – like us – continue to stay with it because this is what we know and can do and don’t have the bandwidth or funds to curate large-scale events that need patronage and sponsorship. The best kind of growth on social media is also one that is organic; that believes in putting out good content and hoping for those who really find value in it to like it and share their comments on it. There are options aplenty to grow the numbers but honestly, what’s the point? Perception, perhaps? Would you like one million fake followers or a handful that truly engages with you in a manner that allows for mutual growth? We just wrapped up a conversation with two young dancers who spoke about how social media in the years of the lockdown opened up possibilities aplenty in terms of networking and opportunities and self-growth. I want to smile because I know that those who are committed to it sincerely, have truly benefited from it; the fly-by-night operators have gone away, already! Maybe they are not meant to stay! And maybe it’s better that way!

Travel Diaries

A first-person account on the culture, tradition, art, life and architecture of the country Bali by dancers of Apsaras Arts, Janani Arun Kumar and Periyachi Roshni. As we entered the cultural heartland of Bali, Ubud, our eyes were transfixed on the intricate soft stone carving in every single house on the street. While other countries strive to become more modern and advanced, this little island places utmost importance to preserving its ancient Hindu culture. Every street, corner and home is deeply rooted in the spiritual and cultural values passed on by several generations. Be it praying everyday, living in a collectivistic culture or respecting and valuing people, nature and art, Bali has managed to somehow retain its personality through globalization. Perhaps the culture, serenity and kindness is what has made this island one of the most sought after holiday destinations. While some might reduce it to the ‘free country’ where parties and merriment are unlimited, there is so much more to this beautiful paradise. The most unique aspect of Bali that caught my eye was definitely their traditional homes. In a large compound a huge joint family resides together. The houses are made of a faded orange brick and lined with carved stone. Each small building in the compound, no higher than a storey or two welcomed us with a balinese wood door. The flowery lace like carving on each door was enhanced with a tint of gold making it look ornate yet classic. The people gave us warm smiles and all you could hear inside the compound was the chirping of the birds in the trees and soft chatter in the compound. The place, although new, still gave me a sense of being at home. As we moved past the living rooms, discussion room, grainery for rice, and a function hall, we were led to the family temple at the north east corner of the compound. While all the other roofs were covered in clay tiles, the roofs on the altars were made of dried hay that had turned a charcoal black with age. The temple hosted altars for the mother temple Besakih, for the family gods and ancestors. As the Balinese do not believe in the worship of statues, each altar was a slender high raised rectangular structure topped with a throne where they believed that their gods would descend if they prayed with utmost devotion. Even the mother temple Besakih hosted the three magnificent thrones for Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva, the Tridatu. Several pilgrims walked up the meandering hills during the Besakih temple festival and waited for hours together to pay obeisance to their gods with flowers, rice and incense sticks placed in a palm-sized leaf basket. They also applied rice to their foreheads, just like a bindi at prayers. The Besakih temple had a huge fleet of stairs leading up to what seemed like a gateway to heaven with two carved stone hedges for doors and the fluffy white clouds against the serene blue sky. The gopuram of the temple stood towering the main entrance that is only opened once a year. All the altars were placed inside the open compound of this gopuram. I am a Hindu and am familiar with the Hindu practices but the way the Balinese approached their rituals in the same religion seemed completely different, until you understand that the significance of these practices are very similar at heart. However, the way the culture is instilled in the younger generations is a testament to their strong yet liberal beliefs and culture. The Balinese way of life is also deeply intertwined with their nature. They cultivate their own grains, the most important is rice. Each home, each temple and each building on the road would have several plants nestled in them in addition to the lush green trees and fields, engulfing the village roads. An air of calm always prevailed around the island and the vast blue sky made it seem as though the whole of this island was under one collective roof. It also seemed as though every corner had an altar and every street had a theater. Art is abundant on this island from streets overcrowded with sculptures, baskets, wood carvings, clothing, paintings, music and dance. Art truly flows in the blood of the balinese and is revered by its people. Being dancers ourselves, we were thrilled to work with the local artists in Bali and gained so many insights into their rich art form. We had the privilege of working and collaborating with Prof Dr I Wayan Dibia and his dance company, Geok ensemble dancers for an upcoming project in November 2022. Geria Olah Kreativitas Seni (GEOKS) is a non-government organization based in Singapadu village of Gianyar-Bali. It is a theater space built by Prof Dibia where we spent most of our time collaborating and learning together. This space also welcomes any controversial and contemporary art and dance and the professor makes it a point to support the young and upcoming choreographers and artistes. Entering the space, we felt a sense of overarching peace as it was situated in the midst of nature and surrounded by traditional Balinese houses including Prof Dibia’s ancestral home. Throughout the choreographic process it was interesting to see, not only how the two dance forms came together but also how the two choreographers Dibia and Mohanapriyan sir tried to find middle ground between their two distinct styles. As it progressed, we learnt that actually there are many similarities between Bharatanatyam and Balinese dance as they both follow principles of the Natya Shastra. For example, the turned out position of the feet, eye and head movements,Trianga is known as Tribhanga in Indian classical dance. Thus, taking these similar traits into consideration it was a fruitful experience seeing how Priyan sir tried to find steps that would correlate to that of the Balinese dance. Another similarity was the using of neck movements attami in Bharatanatyam or using pretitam and chaaris. To our surprise the balinese

Work-in-Process

In conversation with Bharatanatyam exponent, Malavika Sarukkai as she decodes the process of how Anubandh, her latest solo production, came to be What was the genesis of Anubandh? The solo production Anubandh – Connectedness evolved during the last two years. It is an artistic response to the isolation, loneliness, trepidation and fear arising from the pandemic. I needed to express my feelings and observations and the only way I could do that was through dance. Are all ideas of your productions born in moments of solitude and introspection or have there been cases when in the moment of frenetic activity, a thought for a production came your way? An impulse to create can come about quite unannounced. At times, a deep emotional stirring can give rise to a concept which, in turn, transforms into a dance production. And at other times it is a restlessness within, which seeks expression. In my experience at all times the idea persists over a length of time which finally culminates in creative expression. I have learnt over the years that this critical phase cannot be rushed as the concept must mature and evolve naturally. Anubandh was also created in a world that was inherently silent but also there was so much chaos and uncertainty? How do these two contrasting emotions find expression in the work? The world was chaotically silent and in pause mode during the pandemic. It was gravely unsettling. I needed to anchor my observations and feelings. Anubandh grew as a response to find myself individually and collectively in a world of turmoil. The production seeks to reclaim our primordial relationships with the Sun and the Moon, as also with the Five Great Elements, the Pancha Mahabhutas as they are honoured in India – Earth, Water, Fire, Wind and Space. The work re-inforces our deep links with the Great Elements – the generosity of the Earth, the rejuvenating powers of Water, the caressing pleasure (sukha) of the Wind, the unending depth of sorrow (dukha) in Fire, the wonderment in sensing Space and knowing that the same life-breath pervades all. Why is Anubandh special to you and why is it a reminder of the spirit of inter-connectedness? At a deeper level Anubandh is about learning to co-exist and live life with a sense of connectedness and inclusivity. It’s about seeing ourselves as humanity. At a time of uncertainty in a fractured world, Anubandh is a call to the transformative power of hope. What went into the choreography of Anubandh and how tough was it to work with collaborators on an online platform? Working with my team linked only via online calls etc, was exceedingly tough. It was fragmenting as it lacked the warmth of real-time interaction. The only other choice was to abandon the project, which was not an option. Working intensely right through the pandemic was learning to survive keeping the body, mind and spirit alive and purposeful. Anubandh is as much a singular pursuit as it is a collective call for the need to connect with each other, right? How does music play a role in this delineation? The narrative in Anubandh moves from the personal to the shared and from the individual to the collective. The music concept is an area I pay a lot of attention to as I work on creative detailing. Music texturing plays an important role in all my choreographies. Keeping this in mind the coming together of multiple voices, percussion instruments and other instrumentation is a complex and delicate approach, as their needs to be a sense of dialogue with space for silence. Only then does it become a collective enterprise with flow. EOM

#iamayoungdancer

Singapore-based Kshirja Govind and Delhi-based Pritam Das exchange notes on dance and the many beautiful things that are a part of its world. From her home in Singapore and taking time off from a workshop in Bhilwara, Rajasthan as part of SPIC MACAY in West Bengal, Kshirja Govind and Pritam Das, respectively logged onto Zoom to share their stories as young dancers. The conversation began with the dancers discussing the need to be aware of the body as an instrument, the care needed to keep it injury-free and the imperativeness to create awareness on the same. Kshirja noted that the awareness with regard to training and nutrition on social media helped her work on her body in terms of its alignment, posture, etc.https://player.vimeo.com/video/744580964?h=74016726ed Naturally, the topic of conversation segued into social media. Both the dancers admitted that the internet had indeed made the world flat and helped in networking amongst the community and and has undeniably brought dancers together, especially during the pandemic. They discussed the possibilities for dance in the current context and Pritam pointed out that youngsters today are indeed getting a lot of opportunities, thanks to social media and the exposure it has provided. Speaking of the scenario in Singapore and the future of dance there, Kshirja acknopwledged the role of the government and how it not only provides aid in terms of funding, but also arranges many programs and encourages dancers. “There are also programs where children in schools (in Singapore) are exposed to varied cultures and dance forms,” she added. Needless to say, with great power and opportunities comes great responsibility. The two dancers discussed the need for young dancers to have a moral responsibility to try and bring in more viewership to this art form. “One of the main objectives of dancers,” Pritam said, “should be to give back to society in every way possible.” Currently on a tour across rural schools in India under the umbrella of SPIC MACAY, Pritam said this movement aims to take arts to every child of this country. “Meeting these kids, and interacting with them is making them aware of our art forms and seeing the joy it brings to them, is all a very humbling experience.” While the need to perform in traditional performing spaces is crucial, Pritam reflected that experiences like these, to perform in unconventional spaces is also equally rewarding. Unconventional spaces also create more opportunities in the form of workshops, lec-dems, seminars which helps to spread awareness among the people and also helps the dancers to grow with their work. Talking of growth, the two dancers discussed the idea of feedback and criticism. Kshirja agreed on receiving criticism both positive and negative, as few things on dance are subjective while some are purely objective. “I believe that different people’s perspectives are needed to improve one’s own dance,” she said. Pritam insisted on getting feedback from the audience apart from gurus and teachers, as this widens one’s horizons. He also mentioned instances where people have walked up and given him feedback, genuinely like parents do. “I also believe that peers and colleagues can also help each other in one’s growth,” he added. Another interesting discussion was on the topic of collaboration in practicing spaces like Adavu jamming. Both dancers were clearly excited about the idea. Initiatives like these help each other and open up one’s perspectives. Kshirja talked about her collaborative work in performing spaces, but said she had not participated in sessions like these and would love to. One thing is clear; both Kshirja and Pritam are looking forward to opportunities to connect with fellow dancers, in understanding each other’s views, perspectives, sharing their passion, energy and learnings from dance with each other. The conversation finally ended with both the young dancers wondering how this art form would be in a few decades from now! In a good, safe space, hopefully! Kshirja Govind is a Singapore-based dancer and has been learning Bharatanatyam in the Kalakshetra style for over 12 years now. She is learning under Guru P. N. Vikas at Singapore Indian Fine Arts Society (SIFAS). She was awarded the Best Student and ‘Natyavisharad” on completion of her Dance Diploma at SIFAS in 2018. She is also learning at the Upadhye School of Dance and is a company dancer with Apsaras Arts. A regular performer in Singapore for various productions, Kala Vaibhavam, SIFAS festivals, temples, etc, Kshirja also extensively performs abroad in India (Mumbai, Chennai, Bangalore) and around Asia. Her recent performances include solo Bharatanatyam performances at Sri Krishna Gana Sabha for this year’s Ilamayil Thirumai Series and at RK Swami Auditorium as part of Sri Parthasarathy Swami Sabha’s Margazhi Season. She has received many accolades including the Best Performer at Sri Parthasarathy Swami Sabha (119th Year-Dance Festival) in Feb 2019, Prize Winner at the Pravasi Bharatiya Divas 2018, Singapore and the Future Face title at the India International Dance Festival in Bhubaneswar, 2017. Through her collaboration with the Singapore Symphony Orchestra, she has become the first Indian Classical Dancer to receive the honour of working with the SSO. She has been a part of a collaborative performance of Bharatanatyam and Chinese Hokkien Opera at the Chulalongkorn Asian Heritage Forum, Thailand. Pritam Das defines passion for dance through his immense dedication and effortless grace as a Bharatanatyam dancer. Having undergone his initial training under Smt. Jayita Ghosh and Sri Samrat Dutta, he is now under the advanced tutelage of Sangeet Natak Akademi awardee Smt. Rama Vaidyanathan. Pritam has performed both solo and group works as part of his teacher’s ensemble in several prestigious festivals including Spirit of Youth and HCL Concert Series by Music Academy, Uday Shankar Dance Festival, NCPA Mumbai’s Mudra Festival, Dhauli Kalinga Festival, Gudi Sambaraluu, Ustad Alauddin Khan Samaroh, Shivaargya Dance Festival and many more. He is an ‘A’ grade artist of the Doordarshan, an empanelled artist in Spic Macay, and was also awarded the National Scholarship from the Ministry of Culture, Govt. of India for the field of Bharatanatyam

Books Banter

In conversation with V R Devika, cultural activist, storyteller, writer and author of Muthulakshmi Reddy: A Trailblazer in Surgery and Women’s Rights, talks about the journey in documenting the story of this amazing woman and her learnings from it You have been fascinated with Dr Muthulakshmi Reddy for a while now; what was the starting point? After attending the conference titled Text and Context in the York University, Toronto, where Kapila Vastayan had advised me to resign from my school teaching job and make my Bharatanatyam in education programme widely available to other teachers in 1985, I came back and gave a proposal to INTACH, that had just started in Madras with the Madras Craft Foundation as the host. Dr Deborah Thiagarajan liked my proposal and immediately made me the cultural coordinator for the two organizations. Geetha Dharmarajan, (before starting Katha) was a resource person and we jointly began an art in education project at Avvai Home. My interactions there told me a completely different story from the one the academic scholars (mostly from outside) decrying her and Rukminidevi Arundale had been spreading. I dug deeper. Avvai Home requested me for help for a production on Muthulakshmi Reddy. I interviewed her son Dr S Krishnamurthy, her disciple Dr V Shanta, her associate Dr Sarojini Varadappan, for the production which was directed by Pralayan of Chennai Kalai Kuzhu. I decided I needed to tell her side of the story and began writing small articles and giving speeches. When did you know that you wanted to chronicle her life in the form of a book? When I began to study the life of Dr Muthulakshmi Reddy, writing a book on her was never on my mind. I kept looking for more details to look at her life that the academicians of North America had seen with just one angle. ie, taking away the dance from the Devadasi. They cherry picked according to their convenience to support their hypothesis and I had also believed them in the 1980s but working as a volunteer in Avvai Home, talking to several women who wanted their Devadasi lineage hidden and who considered her a Goddess, made me want to look at this a little more. I am telling her story, from her side of the fence. Her story is fascinating. It was when a senior art critic had announced grandly at a talk, he was giving for a dance organization, that “Muthulakshmi, herself a Devadasi, became ashamed of the system when she went abroad and with a stroke of pen made all these women illegal.” He also went on to say that it was on the bodies of these women that freedom was obtained. I was shocked, and decided to share her story wherever I could. It was her disciple Dr V Shanta who urged me to write a new book on Dr Muthulakshmi Reddy. How did you set about doing this? What was the process like? In April 2020, Ramanan Lakshminarayanan, a friend for decades, called and asked me if I was writing a book on Muthulakshmi Reddy. I said I want to, but who will publish it? He said Keshav Desiraju wants to write on her. My ears perked up. Keshave Desiraju, grandson of scholar Dr S Radhakrishnan, former president of India who had just published a fantastic book on MS Subbulaksmi called Of Gifted Voice wants to write on Muthulakshmi Reddy. I knew, I stood no chance against such eminence. I sent an email to Keshav Desiraju. He replied that he wanted to write about Dr Reddy, but he was occupied with research on Tyagaraja at the moment. Then began the hunt for a publisher. After six failed attempts, Mini Krishnan of OUP put me in touch with Nirmalkanti Bhattacharjee of Niyogi and they immediately agreed to publish. They have been the most marvelous to deal with and I am very proud. It is Niyogi that has published the book. Pandemic helped. I sat from April 2020 and wrote furiously. All that I had gathered since 1985 flowed and I knew I had to place her story in context. I learnt more and more as I began to dig and was able to get access to information about her mother. I deliberately decided to quote from Tamil works available on her rather than the academic tenure driven studies on the theme. I needed to tell her story from her side of the fence and I have. I have cut it from a 7,0000 word manuscript idea to 40,000 words to fit into the Pioneers of Modern India monograph series format that Niyogi books decided to publish it under. I am very happy as I want young non- book reading girls in government high schools and colleges to read it. It is accessible to them with its simple narration, I believe. As a writer, and a storyteller and an activist, you are used to documenting people’s lives, already. Was this any different? What were some of your learnings and discoveries along the way? This was fascinating as I learnt about Pudukkottai, its history and geography, the medical college and the history of women in medicine etc as I went along. It was really exciting. This was different as it is a long story as against the brief articles I have been publishing on artists and others. I sent it to five people as I wrote and kept getting valuable feedback. I had hesitatingly asked Keshav Desiraju to look at the manuscript after the fifth draft. He gladly agreed and looked at it meticulously. He sent me the last chapter at 12.30 am on 5th September 2021 (his grandfather’s birth anniversary) He died at 7.30 am. I feel really blessed, though very sad he passed away. I have dedicated the book to him and Dr V Shanta. Why is Dr Muthulakshmi Reddy’s story relevant also in the context of the performing arts? The performing arts are riven with politicking on the act of abolition

#iamayoungdancer

Social Media, Success, Insecurities and Inspiration Two young dancers, Nitya Sriram from Singapore and Nivedha Harish from Chennai, participated in the #iamayoungdancer series this month. Read on to get a sense of what all they talked about… The two dancers – Nitya Sriram and Nivedha Harish kicked off the conversation with the idea of competition that prevails in the world of dance right now. Nivedha, a young Bharatanatyam dancer, musician and a Harikatha practitioner and performer felt that, although there might be healthy competition amongst dancers, there is a constant sense of insecurity, angst, every now and then for dancers paving their way into the world of dance. “I’d say,” Nivedha said, “the only way to get around this is to be confident about oneself and trust your guru and the art form, at large.” Along the same lines, Nitya moved on to discuss the notion of what constitutes as success for young dancers. “With so much content floating around freely on social media and with a steep number of dancers in the playing field and with programs and avenues, aplenty, how does one even attempt to find an answer to this question,” she wondered. “I suppose the only way forward is to be aware of this and negotiate it to lessen one’s own sense of insecurity.” There’s also a positive side to this notion of competition, the duo agreed. “The good thing about it,” Nivedha said, “is that it allows dancers from different backgrounds, banis and parts of the world come together to create work.” Incidentally, the two dancers have also recently bagged the opportunity to work on ARISI: Rice, a production by Apsaras Arts. Speaking of social media, both dancers agreed that that social media in itself has reached a point of saturation on so many levels. “I do think that young minds are being carried away easily with this kind of content,” Nivedha said, “And often this can lead to a sense of dilution and reduction in the attention span amongst the audience, especially with the young audience.” This apart as Nitya added, garnering an audience for in-person performances has become very hard. “Audiences seem to prefer to watch a performance from the comfort of their homes. This can never be like watching a performance live.”https://player.vimeo.com/video/766767643?h=348aa7bf51&badge=0&autopause=0&player_id=0&app_id=58479 The dancers also went on to discuss the onset of dance on film and spoke of how dance can be captured on camera and how this trend has caught on with many artistes. “A whole host of dancers have played around with this idea, thanks to the lockdown and the privilege of time.” They discussed Yavanika, a dance on film by Priyadarsini Govind and seemed in awe of how Priyadarsini had managed to pour so much thought and imagination into the making of the film. Yet another interesting topic of conversation was about the body (of dancers) and the insecurities that often surround that subject. While Nivedha said she often finds a solution to this problem by believing in hard work and her own efforts, Nitya suggested that the fact of the matter is that dance is a very visual medium. She said that as young dancers, one could bring about a change by being more welcoming and less judgmental and accepting all body types. The dancers also discussed injuries for dancers and agreed that yoga certainly helps with overall well-being for dancers, The duo also agreed that it is imperative to focus and take care of one’s mental health in addition to physical well-being. The discussion ended with the dancers stressing the importance of holistic development for a young dancer, which involves watching performances and reflecting on them, reading, and learning from different gurus. Amen to that!

Books Banter

The Voice of the Matter With over five decades of experience, P C Ramakrishna, Chennai-based voiceover artiste, theatre artiste, director, bass section singer in the Madras Youth Choir and pioneer English newscaster, walks us through his book, Find Your Voice. Breaking down voice into science and art, the book is a fascinating treasure trove of exercises to build and nurture the voice and is a reflection on the imperativenes of riyaaz in the context of the arts Find Your Voice is a very powerful title on so many levels; did the title come first and then did you break down the book into its many chapters or did you write the book and then think of this title? The voice has pretty much been the core of my being, one way or another, since I was a schoolboy. With fifty years plus as an actor with the Madras Players, I became more and more conscious of the human voice on stage. For most of these years, we acted in Museum Theatre (non air-conditioned till recent years), windows open, ancient fans making an unholy clatter, and Pantheon Road (Egmore, Chennai) traffic noises filtering through, without mics, and we trained ourselves to be heard clearly. Today’s young theatre actors seem to find it very difficult to be heard without amplification, even though Museum Theatre is now air-conditioned, and the fans relegated to the museum itself. There are many capable actors who conduct acting workshops, but none, if any, who train the actor’s voice. To re-quote the great Laurence Olivier, “You may be the world’s greatest actor, but it is zilch if you cannot be heard”. It is to address this aspect of theatre that I started writing this book. Again, I work parallely in the field of voiceovers, having to read scripts for documentaries, heritage films, and presentations ranging from the severely technical to medical and human interest. It is a rewarding profession which makes its own rigorous demands, perhaps why there are very few in the field. Young, and not so young aspirants have asked me over the years how to enter this profession. This book deals with the niche field of voice-overs. In fact, on request, I am conducting this month a two-day workshop for aspiring voice professionals. This book has a section also on the singing voice. I sing bass with the Madras Youth choir, and I have shared the kind of rigour required for singers to express and retain their voice quality. In sum, I would say that I wrote the book as it came, and the title suggested itself thereafter. You are right, the title goes beyond the demands of just the physical voice, but I wasn’t going to get into that! In the context of the arts, finding your voice, aside from the literal sense of the word, is also very crucial, right? When did you actually find that voice? We don’t get to hear your personal story too much in the book. As I have written briefly in my Introduction to the book, the French, Belgian and Irish priests in the school at Calcutta where I studied discovered this potential in me, even before I knew it. They recognised intuitively that I was more interested in the spoken word and the human voice than the next student, and created opportunities for me to hone my skill. The work I do today to keep the home fires burning is entirely due to their foresight. More than twenty years after I left school, I discovered this profession, and thereby hangs a tale. We love how you have treated voice both from the perspective of science and art; it is the coming together of both, right? Yes. Voice is science plus art. That is why I have dealt with the physics of voice in the first chapter and the chemistry of it in another. However emotive and expressive one is, one can make no impression if the voice sounds like a bullfrog in the mating season. Per contra, you can have a God-given voice, but if you have neither feel nor modulation, no one will listen to you. My take on this would be, a good voice is 40% voice quality and 60% feel. In the chapter on The Chemistry of Voice, you talk about the classical school of acting where the “mind, instinct and the word direct action”. You turn to The Navarasas to elucidate the idea. Tell us a bit about your relationship with the classical arts and how it has shaped your thought, process and performance both as a theatre artiste and a voiceover artiste? There are several schools of acting, as I have acknowledged in the book. The classical style in which I have been brought up works from the mind to the body, as I have detailed in the chapter on ‘Chemistry of Voice’. The Navarasas I have referred to apply to both dance and drama. It is the dramatic element of my training in theatre that has helped greatly in my voice-over work. I have to reach an unseen audience ranging from corporate executives and technocrats to tourists and children. How I reach them through the modulation that makes sense to them is what I have drawn from my theatre experience. The book is also a treasure trove of resources in terms of exercises, tips, strategies in terms of how to cultivate and nurture the voice. This is very generous of you; have you drawn from your own experiences or did you also have to research to write this book? The chapter on exercises is largely from my own experience of what works, bolstered by the tips given by experts that bear out the work I do in this connection. You also talk about the concept of rigour and riyaaz, taking us back to your days in Calcutta, watching maestros practice; why is rigour crucial and what is your own rigour? Riyaaz is a must. Unless the actor or voice over

Cover Story

Dance of the Camera What happens when dance is on film? Do things shift for the artiste and choreographer when they are being seen through the camera’s eye? How do they negotiate this medium to create a work-of-art that is authentic to the dance and to cinema? Three senior Bharatanatyam artitses – Aravinth Kumarasamy, Priyadarsini Govind and Rama Vaidyanathan, reflect upon their dance on film projects and share insights… Read on Rama Vaidyanathan Bharatanatyam Exponent What was the premise of your dance on film, Sannidhanam? Sannidhanam found its birth during the lockdown years; all stage concerts were cancelled. Six of my students were in Delhi cooped up in a hostel. I wanted to engage them meaningfully and also wanted to do something interesting that would make the best use of the situation that we were in. So, when Jai Govinda, dancer-choreographer-curator based in Canada, asked me to present a new work for his online festival, I decided to work on an ensemble production that catered specifically to the camera. What were the significant shifts that you had to make in terms of your dance and the way you imagined dance on screen? Could you share a few examples? The most important thing was the content of the performance, it had to be something which the camera could enhance. I decided to do something on the concept of sacred geometry – the triangle, square and circle – which could be shown dramatically through the camera. Ideally, I would not have chosen this for a proscenium stage. Do you think dance on film has the potential in reaching larger audiences or do you think dance on film was more an intermittent solution to a world that had come to a stand-still where dance did not find expression in the proscenium format. I think dance on film began as a solution to the absence of stage concerts during the pandemic. But in the process, dancers have gone on to realise its potential and have started experimenting with the medium. The possibilities of exploring it artistically as well as the avenues it created for newer and larger audiences was quite overwhelming. I think it has definitely added one more dimension to showcasing dance and is here to stay. What were some of your key learnings by virtue of creating and being part of this dance-on-film? I learnt a lot about camera angles, editing and engaging special lights for the camera. Learning about a different perspective to dance was interesting as well as challenging.——————— Priyadarsini Govind Bharatanatyam Artiste What was the premise of your dance on film, Yavanika? The purpose was to showcase the compositions through the medium of camera. For all of us as artistes, filmmakers and dancers, the potential of movement and especially this kind of trained movements, the variety of our compositions and the depth of abhinaya has to be documented and filmed on for posterity. Dance on film has incredible potential. To me, this is just the beginning. What were the significant shifts that you had to make in terms of your dance and the way you imagined dance on screen? Could you share a few examples? The important thing that I kept in mind was that the production was not seen by an audience seated in front of a proscenium stage.The eye of the camera could travel anywhere. It could take you and direct your gaze to where you want for the audience to see. It could be a small movement of the hand or a formation or the angle at which you want the audience to see the formation or just the pace of the movement of the camera or the details that the camera notes. That was really exciting. Do you think dance on film has the potential in reaching larger audiences or do you think dance on film was more an intermittent solution to a world that had come to a stand-still where dance did not find expression in the proscenium format. I think it has incredible potential and is definitely not a stop-gap solution. What triggered the production was not just documentation. Rather, the camera was another element or a collaborator in the project. That was extremely important. The camera was doing the work of both the dancer and the audience. It was directing the gaze of the audience and registering the movement in a creative and aesthetic way. What were some of your key learnings by virtue of creating and being part of this dance on film? I think the entire working process was a huge learning for me. Our director, Sruti Harihara Subramanian would come in everyday and for the last ten days, Viraj Sinh Gohil the cinematographer and Sruti’s assistant Shiva Krish, the Associate Director would also be there to watch our rehearsals. So the involvement of the director and entire team was 100%. We would demonstrate and Sruti would question and I would do the required changes. Sruti had to divide the shoots, put them on paper, as we were shooting seven compositions in two days and that was not a joke. So everything had to be done like a script to the last detail. I made changes that came out of our discussion till the last four or five days. When you know you are not dancing to the audience but rather to the camera, your mindset also shifts. The possibilities of the formations, what one would want to emphasize on, everything opens up. Right from the start, we were in tune with the idea that this was a dance on film and not a presentation seen on stage.—————– Aravinth Kumaraswamy Artistic Director, Apsaras Arts, Singapore What was the premise of your dance on films? How different were the two from each other? Both these films, Sita and Amara were filmed as CGI films in green screen studios. I believe they were the very first such CGI films featuring Bharatanatyam performance when they were made in 2020. SITA brings to