Work-in-Process

Peeling the Layers… Of female sexual desire… Leading Kathak exponent, Aditi Mangaldas talks about her bold and brave new work, Forbidden, and the story of how it came to be Surely, the idea of Forbidden didn’t happen one day or one night or in a moment, right? But what was that final moment when you decided to distill the thoughts in your head and create a work out of it? Most of my choreographies start off on an autobiographical note, hopefully, eventually opening out in a parabolic universal trajectory; it was the case with Forbidden too. The idea for any production of mine, whether classical or contemporary dance based on Kathak, has always brewed within me for months. If you are open to the pulse of life, then a piece of music, poetry, literature, architecture, movement, nature in its intense beauty and fury, a beautiful painting or sculpture becomes the inspiration and the trigger point. A small seed germinates within your being. For many years I was observing how female sexual desire was trapped in taboos and societal sanctions. Though I come from an extremely liberal family and have lived life mostly on my own terms, these societal taboos do creep in insidiously. The question haunting me was, why is the world scared of female sexual desire? Why are women – the world over – from conservative as well as liberal societies, sanctioned, judged, controlled, hounded, shamed and eventually punished because they have the courage to own their desire? What is the root of this fear? In its very title, Forbidden has a quality of the mysterious in it; something we must not; what was it like for you to explore or traverse into a zone like this? Did you find freedom in the process of this exploration? As women, we grow up realising the taboos attached to female sexual desire – it’s a lived experience, no matter where we come from. As an artiste, I feel compelled to confront these taboos, to acknowledge female sexual pleasure and the ownership of it, which is forbidden. Sexuality is a private affair but all the sanctions attached to it requires and demands taking a stand on the universal, public and personal front. It was not an easy subject, as I realised myself, how deep rooted this fear of female sexual desire was. Quoting the mythologist and storyteller, Devdutt Pattanaik, “… fantasy frightens us, especially female fantasy… One way of regulating fantasy has been by propagating stories where women who pursue their desires are viewed as dangerous, hence need to be restrained for social good.” The process of Forbidden, was like peeling an onion laboriously with every peel making me realise how entrenched this aspect of the forbidden is. In contemporary dance and in the works that you create there is a dramaturg; what is the role of the dramaturg and why is this not yet a prerogative of the classical? For me, as a classical dancer, the aspect of questioning myself has always been interwoven within the repertoire, constantly requiring me to be vigilant. The training, if honestly received, imparts the ability to question oneself fearlessly and critically. Thereby making one their own dramaturg. However, I have not developed this sensitivity when applied to contemporary dance based on Kathak. The dramaturg, in this case Farooq Chaudhry, became the third eye, constantly questioning the intention of every aspect of the production. There is detailed introspection, to ensure honesty towards the work. Female sexual desire is in itself a complex notion to navigate because so little is written or spoken about it for various reasons; what was it like to articulate this in movement? What were some of the challenges you negotiated along the way? The biggest challenge was to confront my own walls, as a woman and as a classical Kathak dancer. The other challenge was transforming these emotions into movement. Forbidden is ferocious and innocent simultaneously. It became a huge challenge to maintain and communicate this duality throughout the piece without unnecessary verbal explanations. I explored many movement vocabularies, slowly letting a tiny essence of them be absorbed within this Kathak being. Forbidden has been realised after months of internalisation, debate, troughs and peaks; as each collaborator offered nuance to the work, till I found myself immersed in it. To create work like this also requires courage; would you like your personality to give your dance that courage or did dance give you the courage to become the person that you are? For me, any production is a two-way process. I would like to be immersed in dance just as much as I would like dance to be immersed in me. Artists are driven to explore subjects that consume them. That drive is a possession which compels artists to face and share provocative and difficult issues. In doing so, their immersion in dance and the dance immersed within their beings is a must and that becomes the fulcrum of the courage that is required for pieces like Forbidden. Lights also play a crucial role in the works that you create; what is the role of lights in this work? I try to encourage the viewer to enter any of my works at multiple and diverse levels. I do not want to put a full stop but like to leave a comma, letting the viewer add their own narrative. For maximising this, all collaborative inputs including light design have a major role to play. It has been a thirty-year dream of mine to work with the legendary light designer, Michael Hulls. Michael was actively involved, not only as a light designer but as a collaborator engaging in all aspects of the work. Only then can a homogenous light design emerge. The lights embody the duality of ferociousness and innocence – they tell a parallel and yet completely in sync narrative of Forbidden. You also acknowledge your mentor here; what is the role of a mentor while creating works like these and why

Books Banter

In conversation with V R Devika, cultural activist, storyteller, writer and author of Muthulakshmi Reddy: A Trailblazer in Surgery and Women’s Rights, talks about the journey in documenting the story of this amazing woman and her learnings from it You have been fascinated with Dr Muthulakshmi Reddy for a while now; what was the starting point? After attending the conference titled Text and Context in the York University, Toronto, where Kapila Vastayan had advised me to resign from my school teaching job and make my Bharatanatyam in education programme widely available to other teachers in 1985, I came back and gave a proposal to INTACH, that had just started in Madras with the Madras Craft Foundation as the host. Dr Deborah Thiagarajan liked my proposal and immediately made me the cultural coordinator for the two organizations. Geetha Dharmarajan, (before starting Katha) was a resource person and we jointly began an art in education project at Avvai Home. My interactions there told me a completely different story from the one the academic scholars (mostly from outside) decrying her and Rukminidevi Arundale had been spreading. I dug deeper. Avvai Home requested me for help for a production on Muthulakshmi Reddy. I interviewed her son Dr S Krishnamurthy, her disciple Dr V Shanta, her associate Dr Sarojini Varadappan, for the production which was directed by Pralayan of Chennai Kalai Kuzhu. I decided I needed to tell her side of the story and began writing small articles and giving speeches. When did you know that you wanted to chronicle her life in the form of a book? When I began to study the life of Dr Muthulakshmi Reddy, writing a book on her was never on my mind. I kept looking for more details to look at her life that the academicians of North America had seen with just one angle. ie, taking away the dance from the Devadasi. They cherry picked according to their convenience to support their hypothesis and I had also believed them in the 1980s but working as a volunteer in Avvai Home, talking to several women who wanted their Devadasi lineage hidden and who considered her a Goddess, made me want to look at this a little more. I am telling her story, from her side of the fence. Her story is fascinating. It was when a senior art critic had announced grandly at a talk, he was giving for a dance organization, that “Muthulakshmi, herself a Devadasi, became ashamed of the system when she went abroad and with a stroke of pen made all these women illegal.” He also went on to say that it was on the bodies of these women that freedom was obtained. I was shocked, and decided to share her story wherever I could. It was her disciple Dr V Shanta who urged me to write a new book on Dr Muthulakshmi Reddy. How did you set about doing this? What was the process like? In April 2020, Ramanan Lakshminarayanan, a friend for decades, called and asked me if I was writing a book on Muthulakshmi Reddy. I said I want to, but who will publish it? He said Keshav Desiraju wants to write on her. My ears perked up. Keshave Desiraju, grandson of scholar Dr S Radhakrishnan, former president of India who had just published a fantastic book on MS Subbulaksmi called Of Gifted Voice wants to write on Muthulakshmi Reddy. I knew, I stood no chance against such eminence. I sent an email to Keshav Desiraju. He replied that he wanted to write about Dr Reddy, but he was occupied with research on Tyagaraja at the moment. Then began the hunt for a publisher. After six failed attempts, Mini Krishnan of OUP put me in touch with Nirmalkanti Bhattacharjee of Niyogi and they immediately agreed to publish. They have been the most marvelous to deal with and I am very proud. It is Niyogi that has published the book. Pandemic helped. I sat from April 2020 and wrote furiously. All that I had gathered since 1985 flowed and I knew I had to place her story in context. I learnt more and more as I began to dig and was able to get access to information about her mother. I deliberately decided to quote from Tamil works available on her rather than the academic tenure driven studies on the theme. I needed to tell her story from her side of the fence and I have. I have cut it from a 7,0000 word manuscript idea to 40,000 words to fit into the Pioneers of Modern India monograph series format that Niyogi books decided to publish it under. I am very happy as I want young non- book reading girls in government high schools and colleges to read it. It is accessible to them with its simple narration, I believe. As a writer, and a storyteller and an activist, you are used to documenting people’s lives, already. Was this any different? What were some of your learnings and discoveries along the way? This was fascinating as I learnt about Pudukkottai, its history and geography, the medical college and the history of women in medicine etc as I went along. It was really exciting. This was different as it is a long story as against the brief articles I have been publishing on artists and others. I sent it to five people as I wrote and kept getting valuable feedback. I had hesitatingly asked Keshav Desiraju to look at the manuscript after the fifth draft. He gladly agreed and looked at it meticulously. He sent me the last chapter at 12.30 am on 5th September 2021 (his grandfather’s birth anniversary) He died at 7.30 am. I feel really blessed, though very sad he passed away. I have dedicated the book to him and Dr V Shanta. Why is Dr Muthulakshmi Reddy’s story relevant also in the context of the performing arts? The performing arts are riven with politicking on the act of abolition

Point of View

Documenting Transitions Vidhya Subramanian, Bharatanatyam exponent, based in Chennai, shares her perspectives on the many shifts – over time – in teaching and learning in the world of dance Krishna transitions from desire to duty, from lover to king, from Gokulam to Mathura, from a life of leisure to the Gita. Change, sometimes abrupt and at other times measured, is a reality of life and transience is the only constant that has potential for growth but also results in loss. Transitions can be both appealing and arduous. I learnt from a traditional nattuvanar, Guru SK Rajarathnam as well as from Kalanidhi (Narayanan) Maami. How I teach today is, in many ways, informed by how they taught and yet also it is an amalgamation of my performance experience, life lived in the US, my move back to Chennai, and my personal negotiations with the art. Pedagogy was organic when I learnt, methodology developing simply from the day-to-day-ness of teaching and learning. Class would start without much preamble, a simple thatti kumbidudhal, and then on to the item/s to be worked on for the next two hours. With Kalanidhi Maami, I was first introduced to dialogue and analysis, although mostly pertaining to the composition being learnt. All through my learning period, there was no analysis of an idea, conversations about inward journeys, articulation of process, not even a warm-up or cool down. All of these, barring the warm-up and cool down, were simply present in the rigour of dancing, a rigour that revealed much more than words, if one had the patience. Lack of patience wasn’t a choice. Teaching became a part of my life at a very early age, courtesy, my move to the USA. As a young teacher away from home, I relied heavily on how I had learnt as a way to teach. Over time, I added warm-up, adavu categorization, theory lessons, accountability sessions, practice logs, strength training, stretching, a handbook, conversations, and social experiences with students. While setting compositions on my students, I chose to focus on the individual and their strengths/weaknesses as a dancer and a human, in part similar to the way I had learnt. The years of dancing, teaching and living in the USA, as well as a Masters with a focus on Bharatanatyam, meant a gradual expansion of methodology and management. Coming back to India regularly revealed that some of my peers in the field were doing the same. Words such as choreography, process, emotional access, relationship with space, balance and so many more we take for granted today, took on a deeper meaning as an entire generation of dancers began searching. Technology somehow both adds to and subtracts from this journey. Today, we have a young dance generation starved to learn, create, articulate, grow and disagree. It is both energizing and joyfully exhausting to engage with many of them. Teaching is an extension of all the work one has been doing so far and a necessary transference of legacy. For me it continues to be focused on the individual, except merged with the conversation that enriches the process. For many young dancers, the cerebral and the corporeal are in a simultaneous pact in the strive for excellence. Once in a while though, it is necessary to silence that head voice and simply dance. To let the emotions surface, to even revel in them, find the silence in them. The transition into an era of abundance has already occurred. As an entire generation of dancers matures in experience, it is important to reflect upon the conflict between duty and desire, to pause and wonder what defines growth and what has perhaps been lost and left behind.

Books Banter

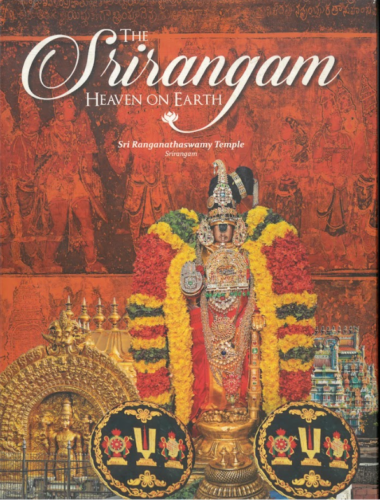

Celebrating Continuity in Tradition Chennai-based historian, writer and author, Dr Chithra Madhavan, an expert in Indian temple architecture, history, sculpture and iconography, shares her thoughts on her book, Srirangam. Srirangam is a fabulous compilation of this temple town; what was your experience of putting it together? The Srirangam temple is an amazing temple-complex which has evolved over many centuries. It is truly a combination of traditional lore, history, architecture, sculpture, inscriptions, rituals, festivals and a whole lot more. It is important to understand that many of the rituals and festivals in this temple are many, many centuries old and are still being practiced today. There has been a continuity in tradition here despite many setbacks. Numerous dynasties have contributed to the architecture and sculpture of this temple. It was a challenge putting this book together, as the different aspects had to be showcased. The contributors have done their best in writing relevant chapters for this book. Without their contribution, this volume would not have been published. As a historian, do you believe that a place never exists in isolation; that its people, culture, society, practices, art, sculpture, architecture all have a crucial role to play? Indeed so. A place can never exist in isolation- there are many factors that make it happen. In times of peace and in times of stress, the reflection is seen on any place and more so in a temple. Rebuilding after an invasion, enhanced social and cultural activities in times of peace, migration of people from other parts of India bringing in their own customs which become entrenched here. These are a few factors that influence the ethos of a place. Srirangam is of particular fascination for classical dance and dancers because of Andal. What aspect of Andal does this book delve into? Andal’s association with Srirangam is well-known. It is here that she merged with God Ranganatha. Her Tamil verses (pasurams) on this deity are many and are recited with fervour even today. There are as many as three sanctums for this Goddess in the Srirangam temple. Many festivals are celebrated here for Andal and she is part of the ethos of Srirangam. This book looks at the different shrines of Andal that are in this temple in the chapters on architecture and sculpture and also many details about this pre-eminent devotee in the chapter on the Azhvars connected with Srirangam. Do you believe also that for any artiste, understanding and appreciating the allied aspects of an idea can help enhance their articulation of a central idea? All of our arts in India are connected. If a performing artist- musician or dancer- wants to sing or dance about Andal, for example, they must know about her life and her association with the different places she was connected with. Likewise, it is mandatory for a historian to know about at least some nuances of allied subjects- literature, music, dance etc. These subjects cannot be studied in isolation. While there has to be a focus on one particular subject, the peripheral ones too need to be studied. This is mandatory. You said this book is extra special to you. Can you tell us why? This book is indeed special to me because first, I am a devotee of God Ranganatha and Goddess Ranganayaki Thayar and also because I am in love with this temple because of its ancient history, architecture, sculpture and inscriptions. This huge temple complex has the largest number of gopurams, the largest number of sanctums, the largest number of mandapams, the largest number of festivals and more than 600 inscriptions. It is a paradise for historians and archaeologists and scholars of religion. It is number one among the 108 Divya Desams (places sanctified by the pasurams of the Azhvars) as eleven of the twelve Azhvars have praised God Ranganatha. For these reasons and more, I’m in love with this temple and so this book is special to me. As a writer and author, does writing each piece or book become a journey of discovery; what was that moment for this book? Indeed, writing or editing each piece or book is a journey of discovery. Since I was not the sole author of this book, but the General Editor (also contributing several articles to it), I learnt a lot from the contributions of the other authors. There wasn’t just one, but several moments of discovery while putting this book together. So many nuances of its tradition like the Araiyar Sevai ritual, the sacred garden from which the flowers are brought to God Ranganatha. So many more were things I did not know much about earlier.