#YoungVoicesinDanceMatter

The Dance India Asia Pacific 2020 kickstarted with a panel discussion titled, What’s Your Voice in Dance with a panel that comprised four young Bharatanatyam dancers — Dakshina Vaidyanthan, Kavya Muralidaran, Manasvini Ramachandran and Mohanapriyan Thavarajah. The conversation was moderated by Aravinth Kumaraswamy, Artistic Director, Apsaras Arts and Akhila Krishnamurthy, Founder, Aalaap. In a fragile, distorted world with an overdose of information and stimulus, the intent of the discussion was to understand the imperativeness of a dance voice and also gain insights on how each of these young dancers is carving for themselves, a unique voice and aesthetic of their own. The discussion began with each of them addressing their instant thoughts of what dance voice in itself means to them — “a medium of expression, an extension of one’s personality, an instrument to become a better version of yourself”. As dancers who are, in a sense, continuing the legacy and identity of their mothers/parents/institutions that stand for a certain aesthetic, the panel also brought to light, the importance of constantly enriching and evolving the dance voice within. Principal Dancer of the Apasras Arts, Mohanapriyan spoke about how his work is deeply enriched by the work of the many legends, stalwarts and their banis, and how it continues to mature with the many perspectives and cross-cultural influences that allow Apsaras Arts to find for itself newer avenues to explore, and unravel. Manasvini Ramachandran spoke about how her study in the area of Conservation has gone onto inform and influence her dance — its context, both tangible and intangible — and the crucial need to find a sense of gay abandon in her dance; the need to “let go” and dance. Responding to a question on the digital mania, Dakshina Vaidyanathan alluded to the importance of discernment on the part of an audience and the need to appreciate the fine line that separates a voice from noise. “If you entered a classroom with children, every child,” she said, “it may be full of noise, but every child there has a voice of its own. Surely, within the mania, there are many voices that need to be heard and appreciated.” Kavya Muralidaran, who carries forward the legacy of her parents/dancers and is in pursuit of a dance voice of her own simultaneously, spoke about the importance of sharing and building a distinct dance voice that is honest, authentic, and soulful at the same time. “Social media is a powerful platform to build for yourself a brand, a voice of your own.” The discussion ended with the dancers responding to a question (from a member of the audience) on the need to use their voice to create work that is reflective of the times that we live in, and use the voice “responsibly” and to make it “inclusive and accessible” at the same time. A voice is an identity; a voice must be distinct but a voice is constantly evolving; for it to be relevant, the voice needs to constantly seek, find, express, share, and always be aware that the arts, like life, is a constant, continual work-in-progress. #youngdancers #bharanatyam #panel #insights #conversations #candid #sharings Tomorrow, September 5, 4.30pm to 5.30pm SGT (2pm to 3pm, IST) Priyadarsini Govind presents The Dancing Body

Mind the Body

The first in the series of webinars curated as part of the Dance India Asia Pacific 2020 that unfolds in a digital avatar this year was The Dancing Body by acclaimed Bharatanatyam dancer-choreographer, Priyadarsini Govind. The session was hosted by Meera Balasubramanian, Bharatanatyam dancer and Company Dancer, Apsaras Arts. Priyadarsini began firstly by acknowledging that the topic was particularly special to her and one that was also particularly relevant in the now. “What I’m going to be sharing,” she clarified at the outset, “is drawn from my own experience of a period of transition where I stopped dancing for a few years and then the uphill struggle that my body went through to be able to get back to my full potential in dance”. As an informal sharing of a very pertinent subject, Priyadarsini began by making a reference to how we are often asked to dance from within/inside. “We often take that for granted or sometimes don’t even realise what that means at a deeper level,” she said, “But it’s only when I returned to my dance, full-time that I started asking myself some important questions that I believe every dancer must know, and be concerned with. What is the body really about; how do you build strength, what is it to perform and what is it to practice? In an attempt to de-mystify that, the lecture was broken down structurally to address the common muscle groups that dancers tend to use. Broken down as posture (referring to the movements in the upper body) and Aramandi (lower body), Priyadarsini’s students, Shweta Prachande and Apoorva Jayaraman — gave a visual form to Priyadarsini’s words, allowing participants understand and appreciate not only the anatomical aspects but also the way we actually apply it in the context of dance. The demonstration brought to fore the importance of stretching and strengthening to practice and perform; the body, as Priyadarsini is a composite of many parts and the need to understand stability and dynamism to be able to dance with freedom, and from within. The grand finale was a performance by Shweta and Apoorva, where they re-created the magic of a song from Tamil cinema in yesteryears. Packed with pace, dynamism, movements and expression, the dance was truly an ode to the dancing body, its potential, and its possibilities. Up next Alarmel Valli in conversation with Aravinth Kumaraswamy, September 5, 8.30pm SGT, 6pm IST

Poetry in Movement

What happens when two artistes — the legendary Bharatanatyam dancer-choreographer, Padma Bhushan Alarmel Valli and the multi-faceted Aravinth Kumaraswamy, Artistic Director, Apsaras Arts — come together to have a conversation? Well, what unfolds is, magic! This session for the Dance India Asia Pacific was hosted by Seema of Apsaras Arts. Excerpts from an interview Looking back, looking forward “Honestly, in my past, I must have done a lot of good to have merited the great masters I’ve had; Titans, as I like to call them. The great, Pandanallur Chokkalingam Pillai and his son, Pandanallur Subbarayan Pillai. They were in a sense, repositories of the collective consciousness of a generation of gurus. They used to take classes in a Corporation school but despite the lack of aesthetics, they created for us a temple of art; there was a sense of divinity in these classes. They stood for high ideals of integrity and commitment. The Pandanallur bani is an ancient bani and perhaps in the hands of a lesser guru, the bani can become straitjacket. But that was not the case with my gurus. They helped build for me a foundation in dance; a foundation of tradition but one that does not stagnate. They gave me the freedom to be my own dancer, to soar and to fly.” An aside from my Arangetram “I must tell you that I performed my Aranegtram when I was just nine-and-a-half; in hindsight, I’m surprised my gurus put me on stage rather early. Honestly, I was a child that didn’t enjoy the publicity. I remember sitting in my room; getting my make-up on and with huge flowers around my hair that was almost heavier than me. What I remember the most though after the Arangetram was the joy on the faces of my mothers and my Masters. And for me, the validation that came from my masters and my mother was the most special.” More than mere lines “We talk often about lines and geometry in dance but really, dance is about the subtexts, the inaffable moments — the twitch of an eyebrow, the flick of a hand, the turn of a head. The truth is that the more we get obsessed with mere physicality, the more likely is for the quality of our dance to go down. Finally, you see, dance is about spontaneity; the unpredictable moments that grow from the training of dance; of moments you yourself have not actually thought about, moments of beauty that are born in the course of the dance on the stage. Dance should go beyond geometry. Dance, for me, is Visual Poetry “You see, poetry is not merely about taking a great poem and interpreting it in dance. The dance has to be poetic and musical. The measure of a complete artiste is the level of musicality in poetry that they bring to their dance. “My engagement with poetry happened very young. My mother and my maternal grandfather — profound scholars in Tamil and English — would read poems to me. They sensitised me to the music inherent in poetry. The constant exposure to poetry and literature sensitised my ear to tone, to the music of language. To be honest, without literature and poetry you cannot become a good dancer.” What makes a Solo Artiste “A solo dancer has to be able to own that space she/he in. I don’t mean that in an arrogant way; what I mean it that it has to become your element in dance. If you do that, you can soar like a bird or dance with all the joy of the wild horses. You will find a sense of freedom and you can be the best you are capable of being. But really, the freedom of being in your element comes with internalisation. As a soloist, you are naked, alone in front of the audience. There’s nothing to detract them. Internalisation comes with more and more practice. The more you practice, the more the dance becomes spontaneous almost as the rhythms of breathing. And once you are free, you have the space to discover; dance then becomes an adventure. But internalisation is a process and calls for sadhana, a tapas. The other imperative quality for a dancer is spontaneity. Practice is integral; sometimes leading up to a performance, I rehearse thrice a day but the rehearsal should not trap you. When you get up on stage, you go on to create dance that grows spontaneously, organically.” My greatest achievement “Perhaps it is the fact that I have, through all my life and its many ups and downs and even as I have negotiated this very trying, testing and sometimes not so pleasant world of dance, been true to the one quality that my mother taught me and that is to be true to myself and to my dance. I’d like to think that holding on to that and continuing to do so will remain my greatest achievement.” Up next The Evolution of the Margam by Dr Swarnamalya Ganesh tomorrow, September 6 at 7pm (SGT), 4.30pm (IST)

Like a rolling stone

“Imagine the evolution of the Margam as a sticky ball,” began Dr Swarnamalya Ganesh, in a tight, well-informed lecture titled The Evolution of the Margam that attempted to focus on the notion of the past, and its fantastic ability to move forward, including along the way a slew of eclectic influences, inspirations and imagination, “Now think of that ball,” she said, “as one that rolls and picks up things along the way; where and when exactly did the ball roll, who really rolled it forward, how many people actually picked it up…What all did they pick up from it and what all did it pick up as it rolled by — languages, cultures, several histories, multiple visions and imaginations.” The metaphor of the ball is particularly crucial and interesting in the context of the Margam for it establishes the imperativeness of the Margam, as Swarnamalya said, as a living, breathing, moving and dynamic entity that doesn’t remain, trapped in a time and an era but one that travels through the course of human history and acquiring nuances in the hands and heads of artistes who decide to add their personal dimensions to it. The solo dancer, Swarnamalya said, in the context of Bharatanatyam, continues to be obsessed, in a sense, of acquiring the Margam. “One she/he learns a Margam, she/he, shifts focus to acquire and learn another. The evolution of the Margam is a journey of human transfer and the very fact that we agree that the Margam is in a process of evolution is testimony that it is an entity with a constant ebb and flow. Swarnamalya’s lecture also focussed on the importance of using words and understanding culture and context, with caution. Tracing back to the 16th century, a period that informed students of human history have access to, Swarnamalya made references to what constituted the structure of what we refer to now as the Margam but was originally created or “culled” as she said by the famous Thanjavur Quartette. The Sadir kutcheri that the Tanjore Quartette performed that we now call the Margam included a repertoire that has undergone shifts and changes, aplenty. The Pre Thanjavur Quartette dances for instance, included dances like the Mukhachali which was similar to the Alarippu but like the Alaru had a dramatic, theatrical entry of sorts. What has also undergone shifts, she said, is the notion of not merely the repertoire but also the stance of the dance itself. For young dancers, it is important to appreciate that the waterterype Margam that we know now, is in itself a story of evolution and that with literature, culture and changing histories. And in its very scope it is meant to expand and assimilate and yet remain inclusive. “The Margam is both an outward and an inward movement.” This session was hosted by Sreedevi Sivarajasingam of Apsaras Arts. Up next Re-imagining the Solo by Malavika Sarukkai

The Dance of Life

When acclaimed Bharatanatyam dancer-choreographer decides to share her journey in re-imagining the solo, you know you are in for some precious lines you want to, as a dancer, remember, and keep re-visiting for life. Excerpts from a lecture Gratitude “When I thought about the title, Re-imagining the solo Bharatnatyam dance performance, I wanted to pause and firstly acknowledge with gratitude the hereditary families and what they have done for us and for the dance. They are really the custodians of this art form; they treasured it, found their dignity through it and brought it to us despite setbacks and despite being marginalised.” The Rigour of Dance “Dance is a rather rigorous, unforgiving tradition. Practising it, day after day, is not easy; it’s a struggle, in fact but struggle is life.” Starting Solo “When I began dancing as a soloist, I must say had to approach it with caution, and with a sense of friendship but slowly I found myself going towards it. After around 15 years or so of training, I slowly started finding that classical dance was slowly starting to becoming a language. It took me a while to arrive at this clarity, so to speak but when I recognise that it was in fact, a vast, expansive language, it opened up for me so many vistas, possibilities allowing me to re-imagine it and turn to my inner voice and ask myself some important questions. Dance is not merely about the aesthetics, the symmetry, the poetry, the metaphor… And then of course the incredible possibility of the adavus itself. Of course, all of this needs to be all this need to be kept in mind but finally it was also about finding a sense of inner alignment. And the more I look within, I began to experience dance as a moment of living vastness.” The importance of intention “Why should dancers ask themselves this question of intention. What is intention in dance. what is my intention? It is honestly the very being. When we change the intention, the awareness, the dance itself changes. The dancing body has many levels — physical, emotional and spiritual and it is all staggering but it’s crucial to locate these different realities within your being. Once that recognition happens and if and when these three strands come together — intertwine, so to speak — the performative becomes the artistic. And what unfolds is, magic! Practice, practice, practice! “Dance is so much about repetition and yet how can we, as dancers, individuals, keep afresh, refresh ourselves, every time we come to practice and perform in a way that we feel it for the first time. I think that quest has propelled me to ensure that despite the demands the dance makes on you, you have to always surrender to it because in surrender, there is strength.” The Individual Feminine: “Khajuraho” “I started re-imagining, Sringaram that is so prevalent (pradhanam) in the Bharatanatyam repertoire, we think of the woman, waiting for her beloved. At some point, early on when I began asking myself some pertinent questions about my dance, I remember seeing a miniature painting of a woman who was bold, passionate, stylised and sensuous. The more I looked at her, the more I was convinced of the need to celebrate her individual feminine desire that was all expansive and universalised rather than a mere coy decoration that is a stereotype of sorts. The Divine Feminine: “Shakti Shaktimaan” “I was initially very cautious to interpret the narrative of the Mahishasura Mardhini; I felt I didn’t have the language to entrust myself to depict her. But some life experiences prompted me to envision her energy and I thought of a sculpture I’d seen at Mamallapuram of the Mahishasura Mardhini and I felt a connection and I felt I was ready to move towards the interpretation. When we look at a sculpture, there’s a lot we can learn about how its maker interpreted it and also the body language of the sculpture itself can tell is a story. Because after all, dance is about observation, people, experiences. Dance doesn’t happen only in the dance class; it happens when you live life and continue to look around.” The Ordinary, Extraordinary Woman: “Thimmakka” “When I read a story of Thijmmakka on a flight, I felt the urgent need to tell the world her story. She was a woman of great spirit and her story is a story of how she changed the course of her life, turning grief into affirmation. I felt I had to dance her story. And let people celebrate the extraordinariness of this human being. The arts is meant to make us empathetic. Outer to Inner: “Laya” “My journey with Laya began with my intention to journey in abstract dance and to work with movement vocabulary to suggest a person who travels from the outer to the inner.” This session was hosted by Vidhya Nair, Apsaras Arts. Tomorrow, September 7, tune in at 4.30 pm — 5.30 pm (IST) for Dr S.Sowmya’s lecture on the Veena Dhanammal’s School of Padams 5.30 pm — 6.30 pm (IST) Rama Vaidyanathan — Tumris in Bharatanatyam

The Aha Moment!

In the first-ever lecture demonstration exclusively focussed on music, Veena Dhanammal’s School (of Padams), the prolific and brilliant musician, Sangeetha Kalanidhi Vidushi Dr S Sowya took the participants of the Dance India Asia Pacific on an hour-long tour of the many qualities that not merely distinguish the Veena Dhanammal bani but also the many aspects that make it sparkle and shine. Befittingly, this session was hosted by young talented and eclectic musician, Sushma Somasekharan. As a musician who had the good fortune of learning from T Muktha (Mukthama) herself, Dr Sowmya focussed her lecture in letting participants appreciate the very “ethereal, addictive almost” quality of this bani which is regarded as a yardstick in terms of its adherence to traditional values and profundity of musical expression. Touching upon three essential aspects — the beauty of subtleties, the importance of brevity and the adherence to tradition — Dr Sowmya extrapolated each of her points with examples from her own repertoire and recalled anecdotes from her own experience of learning from Mukthamma. Speaking about subtleties, Dr Sowmya talked about the importance of listening keenly to appreciate the many layers and nuances this bani is made of. “You have to learn to be sensitive to the music while listening to it; you have to,” she said, referring to the bani, “be an observer and practice listening in between the notes.” Equally attractive is the quality of brevity in the music. “Even the alapana of a ragam like a Thodi or Shankarabharanam, for instance,” she said, “in this school is taut and power-packed. It is the concise nature of the presentation that makes this music so exciting and energetic at the same time.” The brevity is not merely restricted to the very structure and constriction of the raga aalapana or the rendering of a krithi but also in the very spacing of the phrases and in a manner that in singing a phrase, the bani seeks to capture in a moment, the essential quality of the ragam itself. Dr Sowmya also used the metaphor of contrasts and spoke about how just the way we need darkness to appreciate light, the school beautifully emphasised the simplicity of plain notes in a way that people appreciated the ghamakas. In terms of adherence to tradition, Dr Sowmya used the Tamil word, Paadam (the compositions) to highlight the core of this bani that has in a sense, retained and remained true to its legacy and has carefully passed on this music from one generation to another in the hope that even though change is inevitable, it continues to be subtle and seamless. Speaking of the Padams, that are integral to the repertoire of Bharatanatyam, the Veena Dhanammal school has become also synonymous with Padams. But the beauty of these padams, she said, are more than the mere fact that they are so “raga-laden, and full of curves and movements, subtleties and nuances but that it manages to appeal not just to those who appreciate the music but also to the common man who continue to find in it, Aha moments, aplenty! After all, it’s the Aha moments that we continue to seek, right? In the arts, and in life! Up next Thumris in Bharatanatyam by Rama Vaidyanathan

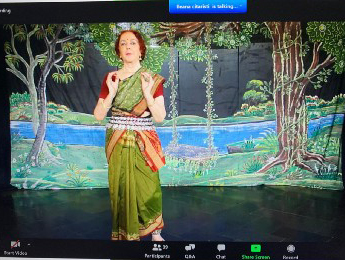

The Dance of Passion, and vice versa!

Who better than acclaimed dancer, Rama Vaidyanathan, who in her own words, called herself a perfect amalgam, a “hybrid of the North and South Indian culture of India” to capture and bring alive the essence of the thumri and her own journey with incorporating it into the vocabulary of Bharatanatyam. In a pre-recorded session where Rama Vaidyanathan shared stage with a bunch of eminent musicians — Dr Nabanita Chowdary on vocals, Mithilesh Kr Jha on tabla and Sumit Mishra on harmonium — the lecture demonstration literally transported the viewer to the court of Wajid Ali Shah of Lucknow, in whose period, somewhere in the 19th century, the thumri that literally is born out of the Hindi word, “thumakna” (meaning to move) found its genesis. It’s perhaps got to do with the curation mastery of Aravinth Kumaraswamy that Rama Vaidyanathan’s session was soon after Dr S Sowmya’s session on the Padams of the Veena Dhanammal bani. Rama Vaidyanathan drew interesting parallels between these two traditions reinforcing how they grew and became popular almost at the same time in two different cultures but were performed inherently by the courtesans who belonged to the hereditary families. “If you look at the Padam and the Thumri, you will notice they are both rich in poetic content with an accent on lyrics both the singer and the dancer attempt to portray subtle and varied shades of the meaning of the poetry which is usually focussed on the intimate, passionate moments with the lover, of a god who becomes a lover and of pining for a beloved who is sometimes the Lord; the speed or the pace is usually slow except the thumri picks up pace towards the end with the tabla. For me, these similarities across two cultures is a huge unifying factor in the history of Indian classical dance.” “As a dancer,” Rama said, “who studied Bharatnatyam in Delhi but grew up with access and exposure to Kathak and Hindustani music, I continue to be fascinated by the versatility of the Bharatanatyam idiom and its ability to transcend boundaries of language, musical genres, and cultures to come alive and create powerful pieces of poetry.” To demonstrate this idea and to allow us understand and appreciate how the thumri weaves into the fabric of Bharatanatyam, and so seamlessly, Rama Vaidyanathan demonstrated two beautiful thumris. Here’s an excerpt from a thumri is raag Pilu composed by the outstanding Bade Ghulam Ali Khan sahab of the Patiala gharana. The central motif here is that of laughter; as a friendly fight between Krishna’s friends and Radha’s friends, the thumri in Rama’s world sparkled with a joyous personality. As a stark contrast to that, in raag Shivaranjani, the second thumri, Ro Ro Nain Gavaye, brought to fore a heroine who has been scorned by her lover who doesn’t show up as promised; forcing her to pine and grieve even as she burns ragingly in passion, wondering about a youth going wasted — Umariya beeti jaaye. For a Bharatanatyam dancer, who is trained, honed and groomed to dance the padam, being able to portray the vipralabdha nayika (one deceived by her lover) isn’t new. But to understand it in the context of another context and culture, and dance in a way that the beauty of the language, the poetry and a musician from another genre, feel truly justified to find expression in a dance form that is unfamiliar with them all, is the genius of an artiste who owns her instrument, is multi-cultural and above all, one who has the unique ability to find similarities in differences, and vice versa and celebrate them all in her dance. A dance of freedom, of sensuality, of unbridled emotions, of passion, of life! This session was hosted by Seema of Apsaras Arts! Up next tomorrow 8 September — 4.30 pm — 5.30 pm : Chitrasena Dance Company — Kandyan Dance 8 September — 5.30 pm — 6.30 pm : Dr Srilatha Vinod and Anjana Anand — Silapathikaram — Dancer’s delight

Soul of the Soil

For the first time ever, in the history of Apsaras Arts’ Dance India Asia Pacific, participants were privy to a session exclusively dedicated to the history, practice and performance of Kandyan Dance by the Chitrasena Dance Company. Introducing the session, DIAP’s Curator, Aravinth Kumaraswamy said that it was a matter of great pride for the dance that belongs to the country he hails from — Sri Lanka — finds a platform on a global stage and the possibility of participants to appreciate the beauty and nuances of this brilliant dance form. Helmed by Heshma Wignaraja, Artistic Director of the Chitrasen dance company and its resident choreographer, whose grandfather was the legendary Chitrasen, founder of the dance company, and whose grandmother, Vajira, who began her journey as Chitrasen’s pupil, his partner on stage and off it thereafter and went on to become the prima ballerina of dance in Sri Lanka. Breaking the lec-dem into two parts, Heshma first touched upon the history of Kandyan dance referring to how it began as a ritual of sorts nearly 2500 years and originally had a mythical quality associated with it. Over time, in villages, the repository of the dance grew in the tradition of oral history and Kandyan dance evolved into becoming a dance ritual of sorts. In the early 30 and 40s, as society became organised, the dance found its way to modern stage. Chitrasena’s contribution, as Heshma pointed out was to distill the dance form from the rituals and infuse in them a sense of theatre in a manner that it became accessible to contemporary audiences. “Honestly, the genius of Chitrasena is that he didn’t seek to transform traditional dance forms,” she said, “In his world, new was an extension of the old.” The Chitrasena Dance Company was also instrumental in breaking barriers of caste, and gender barriers on stage. A pure, abstract dance form, without a linear narrative, Kandyan dance, was originally only performed by males and it’s ironical that today, there are more women who practice this form. The partner of a dancer in this dance form is undoubtedly the drums. Likening to the idea of a marriage, where one partner is incomplete without the other, Heshma spoke about how for a dancer to really understand her dance, it is imperative for her/him to understand the body of the drum and therefore translate that in movement. The second half of the demonstration was focussed on allowing participants appreciate not merely the many parts that comprise the language and vocabulary of this dance but also the process that goes into training dancers into being performers, on stage. Starting from the stance, the five central positions of the arms and the feet, the patterns it draws in space, the sentence structures, the way paragraphs find expression, the beauty and the strength of jumps, the recorded demonstration by Thaji Dias, Principal Dancer of the Chitrasena Dance Company gave audiences a crystal-clear sense of the language of this form. Demonstrating jumps in Kandyan dance Another excerpt from the demonstration by Thaji Dias Needless to say, to appreciate nuances, one has to dig further. But if the framework in itself is as powerful as what we saw, one can only well imagine how poignant and magnificent its soul would be! Up next Silapadikaram- Dancer’s Delight by Dr Srilatha Vinod & Anjana Anand

Stream of Consciousness: Dance of Human Conscience

What makes the Silapathikaram, the epic Tamil text a dancer’s delight? Why do dancers keep returning, time and again, to engage, and immerse themselves in this text to find new meanings and metaphors in it and translate those nuances in their dance? This session was conduced by the sensitive and talented dancer, Mohanapriyan Thavarajah, Principal Dancer of the Apsaras Arts. In a two-part lecture handled by Anjana Anand and Dr Srilatha Vinod, this text, yet again, came alive in all its beauty and glory. “There’s a storehouse of information in this text from every perspective,” said Anjana Anand, referring to her own love for the Silapathikaram, both from the point of a view as a dancer and a researcher, “As one of the greatest Tamil epics, and as a rasika of literature, first and foremost, one can find in it, an array of emotions — love, romance, heroism, revenge, dharma; it’s a true story of human struggle and also a powerful epic to document the three kingdoms of the Tamil country — Cholas, Pandyas and Cheras.” Anjana said she was only exposed as a dancer to Sanskrit literature but deep diving into the Silapathikaram allowed her the possibility to understand not merely the text and language but also a piece of Tamil’s cultural history. For the demonstration, Anjana chose to depict eight verses from the Kaanal Vari, the 7th canto in the first book. In it, you hear both the voice of Kovalan and Madhavi. This canto is interesting also because it’s a turning point of sorts in the text, when the “seeds of distrust shown on Kovalan’s heart have become like wheels strangulating their love”. Demonstrating five verses from this section, set to different ragams and capturing the many rasas each verse is layered with, Anjana’s demonstration also highlighted key aspects that go into a dancer determining to choose text to adapt it to her dance. “Is all poetry adaptable for stage? if so, how do we go about choosing it? she said and shed light on three crucial aspects amongst them a) Does the poetry have an inherent rhythm which makes it easier for a musician to set it to music? b) Imagery in the text; does it have an inherently visual quality to it for a dancer to play around with it? c) Dhwani or resonance; does the poetry allow the dancer to have multiple thoughts; is there something in the poetry that remains unsaid? For honestly, if there’s not, where would the dancer really be? Dr Srilatha Vinod, who has engaged time and again with the Silapathikaram chose to shared three poignant and powerful excerpts from her production on the Silapathikaram that premiered way back in 2004. Srilatha’s choice of the excerpts not only brought to fore the crucial turning points that make this text so classic and timeless at the same time but also was a true ode to the potential of dance to be able to create visual poetry on a bare stage with nothing but lyrics and music for company. It is the mastery of an artiste to identify — in the half a hour allocated to her — verses from a masterpiece that allow audiences, familiar and unfamiliar with the text, to get a glimpse of the potential and possibilities of the epic and of the dance to keep engaging with it. Befittingly, the first section paid obeisance to the sun and the moon and Srilatha chose the final excerpt also to be the sequence where Kannagi turns to the sun and the forces of nature to seek justice when she hears of the treacherous treatment meted out to her husband, Kovalan. The middle section we watched was the stunning dream sequence where Kannagi has a premonition of a tragedy that is round the corner, waiting to befall. Srilatha’s performance that premiered at the Koothambalam in the Kalakshetra and where she worked closely with an artiste called Unnikrishnan, also trained in the Kalakshetra to create this work, is a timeless depiction of a text that has withstood the test of time and continues to inspire and invigorate dancers. But like Srilatha rightly said, “The epic demands deliberate introspection of characters and of the storyline, else it is a very tall mountain to climb!” Truly so! But a dancer’s delight, nonetheless Up next 9 September — 4.30 pm — 5.30 pm : Dr Ileana Citaristi — Sancharis in Odissi 9 September — 5.30 pm — 6.30 pm : Aditi Mangaldas — Re-Imagining dance during lockdown (IST)

Between the lines…

On Day 5 of the Dance India Asia Pacific 2020, Padmashri Dr Ileana Citaristi took participants on a journey of sancharis in the world of Odissi. Drawing from her own rich experience in traditional and experimental theatre from her place of birth, Italy, followed by her extensive training and mentoring in Odissi by the legendary Guru Padma Vibhushan Kelucharan Mohapatra and Chhau Guru Sri Hari Nayak, Ileana brings to the stage shed light through a series of excerpts the concept of sancharis in the context of the dance she literally owns — Odissi. This session was hosted by Soumee Dee, an Odissi dancer and teacher at Apsaras Arts. Explaining the concept of the sanchari bhava, Ileana allowed participants to deep dive into the process of how a choreography with a central abhinaya and emotion lends itself to the possibility of “amplifications and auxiliaries that support and complement the main subject or the sthayi brava that the composition is laden with”. Dance, after all, is about reading not a poem as it is, but reading in between the many lines that it’s made up of and using her/his imagination, and creativity to layer the narrative with expressions and subtexts that are subservient to the sthayi brava but accentuate it, nonetheless. Her presentation comprised three excerpts from legendary Odissi exponent, Guru Kelucharana Mohapatra’s choreographies. The first excerpt was from the Ashtapdi, Yahi Madhava and brought to light a Radha who waits patiently and passionately for Krishna to arrive; she is adorned with garlands, the bed is full of flowers and studded with decorations, she waits for Krishna to arrive but when he does the morning light has almost arrived and it’s evident that he has spent the night with another woman. How does one therefore expand this narrative, the conversations, spoken and unspoken between the two, in a way that the pain Radha’s pain is enforced in a way that the dance becomes a visual allegory. Dr Ileana also spoke about the principle of inclusion and expansion. While working on sancharis, it is important for a dancer to not only understand the context of the narrative well but also to think deliberately upon how much to include and what really to expand upon. Her second excerpt was from the Ashtapadi, Sakhi Re, where Radha tells her sakhi to go and fetch Krishna as she is full of desire. And in a typical way that friends converse and like to share details of their many adventures, big and small, Dr Ileana used sancharis sensitively to create for the audience an atmosphere of that secretive-ness and suspense that makes her little exploits with Krishna so fun and exciting. “One has to look carefully within the poem to understand what the poet is trying to actually elaborate and go beyond the literal translation of the meaning of the poem.” After all, dance is all about the possibilities and in the world of a genius like Dr Ileana Citaristi, those possibilities become endless, and timeless at the same time. Up next Re-imagining Dance during the lockdown by Aditi Mangaldas