Dance of the Camera

What happens when dance is on film? Do things shift for the artiste and choreographer when they are being seen through the camera’s eye? How do they negotiate this medium to create a work-of-art that is authentic to the dance and to cinema? Three senior Bharatanatyam artitses – Aravinth Kumarasamy, Priyadarsini Govind and Rama Vaidyanathan, reflect upon their dance on film projects and share insights… Read on

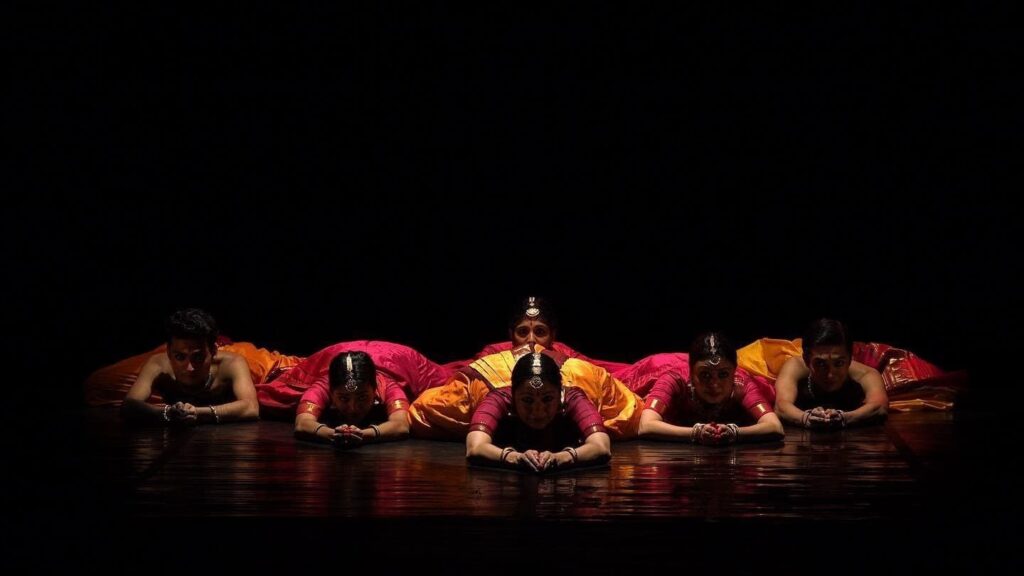

Rama Vaidyanathan

Bharatanatyam Exponent

What was the premise of your dance on film, Sannidhanam?

Sannidhanam found its birth during the lockdown years; all stage concerts were cancelled. Six of my students were in Delhi cooped up in a hostel. I wanted to engage them meaningfully and also wanted to do something interesting that would make the best use of the situation that we were in. So, when Jai Govinda, dancer-choreographer-curator based in Canada, asked me to present a new work for his online festival, I decided to work on an ensemble production that catered specifically to the camera.

What were the significant shifts that you had to make in terms of your dance and the way you imagined dance on screen? Could you share a few examples?

The most important thing was the content of the performance, it had to be something which the camera could enhance. I decided to do something on the concept of sacred geometry – the triangle, square and circle – which could be shown dramatically through the camera. Ideally, I would not have chosen this for a proscenium stage.

Do you think dance on film has the potential in reaching larger audiences or do you think dance on film was more an intermittent solution to a world that had come to a stand-still where dance did not find expression in the proscenium format.

I think dance on film began as a solution to the absence of stage concerts during the pandemic. But in the process, dancers have gone on to realise its potential and have started experimenting with the medium. The possibilities of exploring it artistically as well as the avenues it created for newer and larger audiences was quite overwhelming. I think it has definitely added one more dimension to showcasing dance and is here to stay.

What were some of your key learnings by virtue of creating and being part of this dance-on-film?

I learnt a lot about camera angles, editing and engaging special lights for the camera. Learning about a different perspective to dance was interesting as well as challenging.———————

Priyadarsini Govind

Bharatanatyam Artiste

What was the premise of your dance on film, Yavanika?

The purpose was to showcase the compositions through the medium of camera.

For all of us as artistes, filmmakers and dancers, the potential of movement and especially this kind of trained movements, the variety of our compositions and the depth of abhinaya has to be documented and filmed on for posterity.

Dance on film has incredible potential. To me, this is just the beginning.

What were the significant shifts that you had to make in terms of your dance and the way you imagined dance on screen? Could you share a few examples?

The important thing that I kept in mind was that the production was not seen by an audience seated in front of a proscenium stage.The eye of the camera could travel anywhere. It could take you and direct your gaze to where you want for the audience to see.

It could be a small movement of the hand or a formation or the angle at which you want the audience to see the formation or just the pace of the movement of the camera or the details that the camera notes. That was really exciting.

Do you think dance on film has the potential in reaching larger audiences or do you think dance on film was more an intermittent solution to a world that had come to a stand-still where dance did not find expression in the proscenium format.

I think it has incredible potential and is definitely not a stop-gap solution. What triggered the production was not just documentation. Rather, the camera was another element or a collaborator in the project. That was extremely important.

The camera was doing the work of both the dancer and the audience. It was directing the gaze of the audience and registering the movement in a creative and aesthetic way.

What were some of your key learnings by virtue of creating and being part of this dance on film?

I think the entire working process was a huge learning for me. Our director, Sruti Harihara Subramanian would come in everyday and for the last ten days, Viraj Sinh Gohil the cinematographer and Sruti’s assistant Shiva Krish, the Associate Director would also be there to watch our rehearsals. So the involvement of the director and entire team was 100%.

We would demonstrate and Sruti would question and I would do the required changes. Sruti had to divide the shoots, put them on paper, as we were shooting seven compositions in two days and that was not a joke. So everything had to be done like a script to the last detail. I made changes that came out of our discussion till the last four or five days.

When you know you are not dancing to the audience but rather to the camera, your mindset also shifts. The possibilities of the formations, what one would want to emphasize on, everything opens up. Right from the start, we were in tune with the idea that this was a dance on film and not a presentation seen on stage.—————–

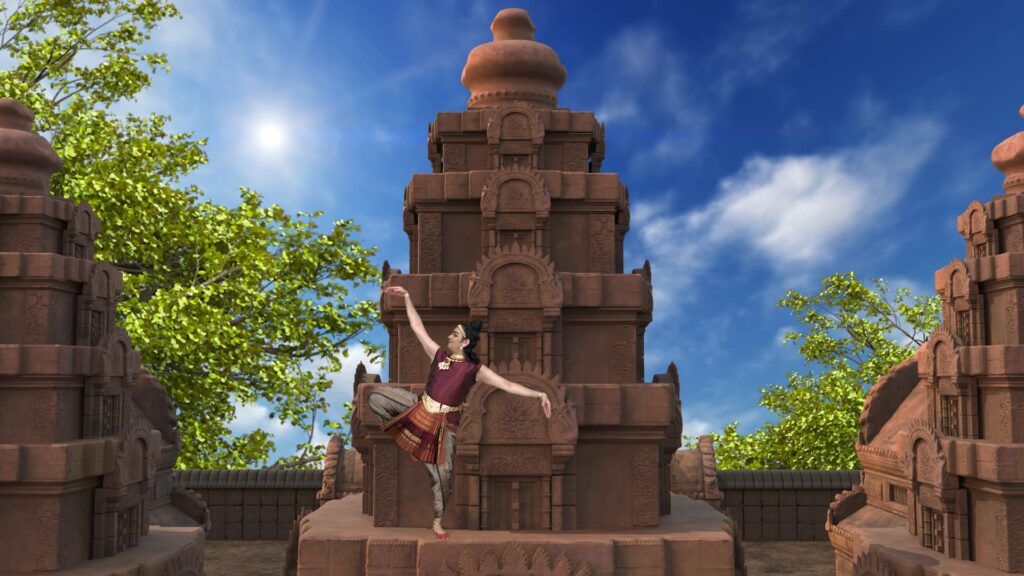

Aravinth Kumaraswamy

Artistic Director, Apsaras Arts, Singapore

What was the premise of your dance on films? How different were the two from each other?

Both these films, Sita and Amara were filmed as CGI films in green screen studios. I believe they were the very first such CGI films featuring Bharatanatyam performance when they were made in 2020.

SITA brings to life, selected paintings of the Ramayana heroine, Sita as painted by Raja Ravi Varma. As a result, the paintings become the setting against which the dancers perfrom the characters including Sita, Rama, Ravana, et al.

AMARA brings to life the epics carved on the bas-reliefs on the walls of the beautiful Khmer monument, Banteay Srei in Cambodia. Here, CGI technology was used to create a digital set of the monument, its walls, domes, towers, doors and passageways, in which the dancers performed.

What were the significant shifts that you had to make in terms of your dance and the way you imagined dance on screen? Could you share a few examples?

The significant shift was to perform to different camera angles, repeating each sequence inside a virtual set. A green studio has its walls, floor and ceiling all in green. Hence the sense of direction is all imaginary and virtual, which makes it harder for the dancers, giving them an additional layer of challenge.

Do you think dance on film has the potential in reaching larger audiences or do you think dance on film was more an intermittent solution to a world that had come to a stand-still where dance did not find expression in the proscenium format.

Given that the world learned to consume and appreciate art on the digital medium during the pandemic, we have built new audiences and transformed some of the traditional audiences. However, the expectations of digital audiences is to look out for new content specifically produced for digital media, and not be offered recycled videos of earlier stage performances.

As such when we conceived fresh content using digital technology with CGI, both Sita and Amara were well-received. We believe a new market opportunity is here to capture, grow and stay.

What were some of your key learnings by virtue of creating and being part of this dance on film?

All elements of the work including choreography for camera, costume design for digital media, sound quality of music are key for digital dance-on-film. Most importantly, the concept has to be for film media, which is very different from stage performances.

The film director who envisions and directs the camera crew and oversees the post-production is as important as the choreographer. All elements of the work need to be produced for the medium on which it is produced and consumed.