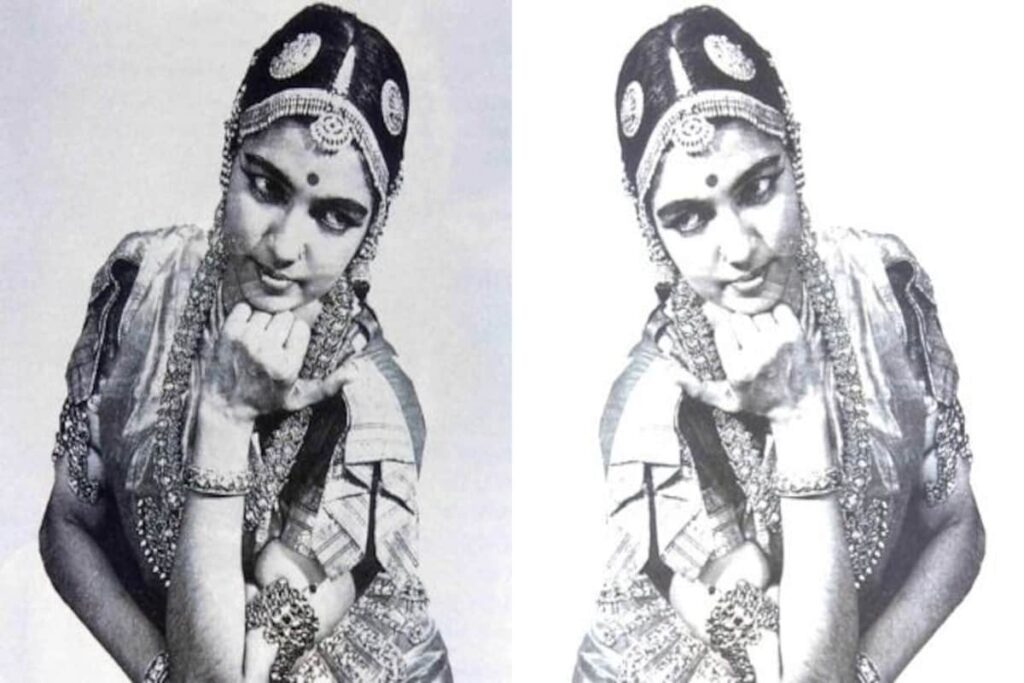

By Dr V.R Devika On Rukmini Devi Arundale’s 117th birth anniversary, it is perhaps time to re-evaluate the scathing remarks relentlessly brought against her and her contributions to the world of Indian classical dance, Bharatanatyam in particular. “The Devadasis and others who danced, whatever their customs, whatever the circumstances in which they lived, they were people with devotion, they were excellent artistes. Even today, they really are the people from whom we can get the best ideas in Bharatanatyam. I must pay my tribute to them.” — Rukmini Devi Arundale’s demonstration talk at the National Dance Seminar in Delhi, 1958.

Revisiting this and several other such statements of Rukmini Devi Arundale (29 February 1904 – 24 February 1986) becomes essential as one re-reads the relentless remonstrations by scholars against her alleged “sin” of Bharatanatyam “revival”, along with its “re-vivication, re-population, re-construction, re-naming, re-situation, restoration,” as posited by Mathew Harp Allen in his “seminal” essay Re-writing the Script for South Indian Dance. While remembering Rukmini Devi on her 117th birth anniversary, one is also reminded of a survey done by some on her, Mahatma Gandhi and Dr Muthulakshmi Reddy. In this regard, the highly “educated” are guarded and give ambiguous replies on ideologies, while the working poor talk about how difficult and challenging it must have been for these pioneers to chart a completely new course, inspite of being in privileged circumstances that could have given them a comfortable life. Today, it is perhaps time to re-evaluate those scathing remarks relentlessly shot at Rukmini Devi Arundale. Amrit Srinivasan, in her essay Reform or Conformity, says that when Muthulakshmi Reddy’s bill of 1930 — that sought the abolition of temple dedications — finally came to be passed into law in 1947, it seemed to have been pushed through not so much to dole out death to the Tamil caste of professional temple dancers, as much as it was to approve and permit the birth of a new “elite” class of performers. She speculates that this happened because of the support from the Theosophical Society that Rukmini Devi — who, along with her husband were its members — received, and she learnt dance and established Kalakshetra, an institute that “had been set up to restore the ancient glory of India and to counter the western Christian morality and materialism”. However, it was not the Theosophical Society, but social activist and politician Periyar EV Ramasamy and the Justice Party of Madras who supported the Anti-dedication Bill of Muthulakshmi Reddy. Reddy, an insider, who knew what it was to grow up with the stigma accorded to her community, introduced and fought for the bill, empowered by her modern education and position, with a trajectory akin to that of BR Ambedkar’s. In fact, there were many members of the Theosophical Society who had objected to the establishment of Kalakshetra in the Society’s vast campus. By 1947, Kalakshetra was a fully functional institute in the Theosophical Society campus with Mylapore Gowri Ammal, the last Devadasi of Mylapore Kapaliswara Temple teaching there. Dancer and actress Kumari Kamala (later Kamala Lakshman), who had danced her way into the hearts of millions with her dance performances in films and was especially popular among middle class families, sought out traditional nattuvanars to teach her young daughters. By that time, Raja Rajeshwari Natya Mandir had started teaching Tanjore Bharatanatyam in Mumbai. Mrinalini Sarabhai, Shanta Rao and Ramgopal had gone to the village of Pandanallur in Tamil Nadu to learn dance from the doyen Meenakshi Sundaram Pillai. Each of them had begun to create their own styles of dance, and there was no need for an act to explicitly facilitate this. Historically, re-vivication and re-construction of the dance has happened continuously. We learn that 18th century dynastic musicians had already set in motion the reconstruction and formation of the adavus (basic units of Bharatanatyam) as listed in the Sangītasārāmrta. The famous Thanjavur Quartet redesigned and refined the adavusystem and composed a solo repertoire (Margam) with the foresight of performance at spaces outside the king’s court. “If at this time, an infrastructure for courtesan art to flourish had been negotiated, the courtesan’s art would have travelled entirely differently through the troubling times of disintegrating kingdoms, and the uprising anti-nautch movement of the late 19th century and early 20th century,” says Jeetendra Hirschfeld who has researched the dance form’s history. Meenakshi Sundaram Pillai, who taught Rukmini Devi, was nervous about her first performance for the annual convention of the Theosophical Society in 1935, even though it was not an arrangetram, but a small showcasing of the usual dramas. He sent his son Chokkalingam Pillai to conduct the nattuvangam for this programme. “Meenakshi Sundaram Pillai was quite relieved with the response to the performance and he continued to teach me. Later, when he wanted to get back to his village, he sent Kattumannar Koil Muthukumara Pillai,” Rukmini Devi said. Appropriation of Devadasis’ dance to re-populating it with new “Brahmin” amateurs is another charge brought against Rukmini Devi. Professor S Swaminathan, who grew up in Pudukkottai, says that upper caste amateur musicians were always there. He can count 10 generations of serious amateur musicians in his family. Rukmini Devi invited the great veena player Karaikudi Sambasiva Iyer from this family to teach in Kalakshetra. Her own family had generations of musicians on her mother’s side, so it was not a surprise that middle class girls, boys and several non-Indians took to learning the art when it was available to them. Rukmini Devi Sanskritised and sanitised the dance is yet another allegation brought against her. However, the karana poses depicted in the 10th century temple of Brihadeeswara in Thanjavur, where the art was nurtured, are all from the Sanskrit treatise Natyashastra. Rukmini Devi said: “When I put questions about the meanings of gestures to my teacher Meenakshi Sundaram Pillai, he was able to give me the meaning of the shlokas as he was a learned man.” Therefore, the gurus have traditionally always followed Sanskrit texts as the foundation of the dance. An essay dated 1806 by P Ragaviah talks eloquently about textual influence of Sanskrit on the dance of the Devadasis. Meenakshi Sundaram Pillai had helped Rukmini Devi set the syllabus and the training methodology at Kalakshetra. Additionally, Rukmini Devi is also criticised for renaming the dance. “The solo recital of Bharatanatya used to be called Sadir kutcheri, which had its own associations because of which I preferred to call my recitals Bharatanatya,” Rukmini Devi said. The first time she had seen “Bharatanatya” (she does not mention it as Sadir) was in the Pudukottai Temple procession, when she was a little child. But it was when she was in her 30s that she witnessed the performance of Jeevarathnam and Rajalakshmi at the Music Academy, and was mesmerised, only to want to learn the dance form. She did not invent the name but preferred using Bharatanatyam from among the other names. Mathew Allen further writes that Rukmini Devi Arundale, along with E Krishna Iyer, quite deliberately moved the dance away from the temples. In reality, Rukmini Devi argued for the dance to remain in the temples. He also criticises her for keeping an icon of Nataraja on the right side of the stage. The inspiration for her to keep the Nataraja on the stage came after she had danced in front of the sanctum at the Nataraja temple in Chidambaram. This is what she said in a speech: “At the diamond jubilee programme of the society, we had expected about 200 people but 2,000 turned up. There was so much excitement. More than anything, it totally changed people’s perception about the dance. I wanted to carry the work further and start giving shape to my own ideas on Bharatanatyam. But before starting, I wanted to go to Chidambaram and dedicate myself to the lord of dance, Shiva. VS Srinivasa Sastri arranged it for us. Though normally nobody was allowed to dance inside the main prakharam, we went quietly without making much noise. When we reached there Srinivasa Sastri came running to warn us.” “Don’t go in, there is a crowd of more than a thousand. You will get mobbed. Somehow, the word had got out about the dance. But having come, I did not want to go back. So we went in. There was a frightful rush. Our party was pushed and we all got separated. I somehow got in front of the main shrine and I shouted to my musicians to start singing and playing wherever they stood. I did just an alaripu as my offering and as I danced, I moved backwards and managed to get out of the temple. It was a great moment. The hard stone floor of the temple was soft to my feet like a bed of flowers. It was a great spiritual experience. I felt I now had the God’s blessings to start the work I had in mind…” She made an aesthetic choice of décor for her dances and the dance world imitated her. Rukmini Devi Arundale re-situated the dance and set up a traditional space for its training amidst nature, clothing it in handloom, pure colours and texture, jewellery and handicraft that deserved to be celebrated. She used the unique position she found herself in to tap into and revise the regenerative resources of the tradition of dance, reinterpreting it in her creative way. Like water, the art found its level instead of drying up. Published on Firstpost on 26th Feburuary 2021.