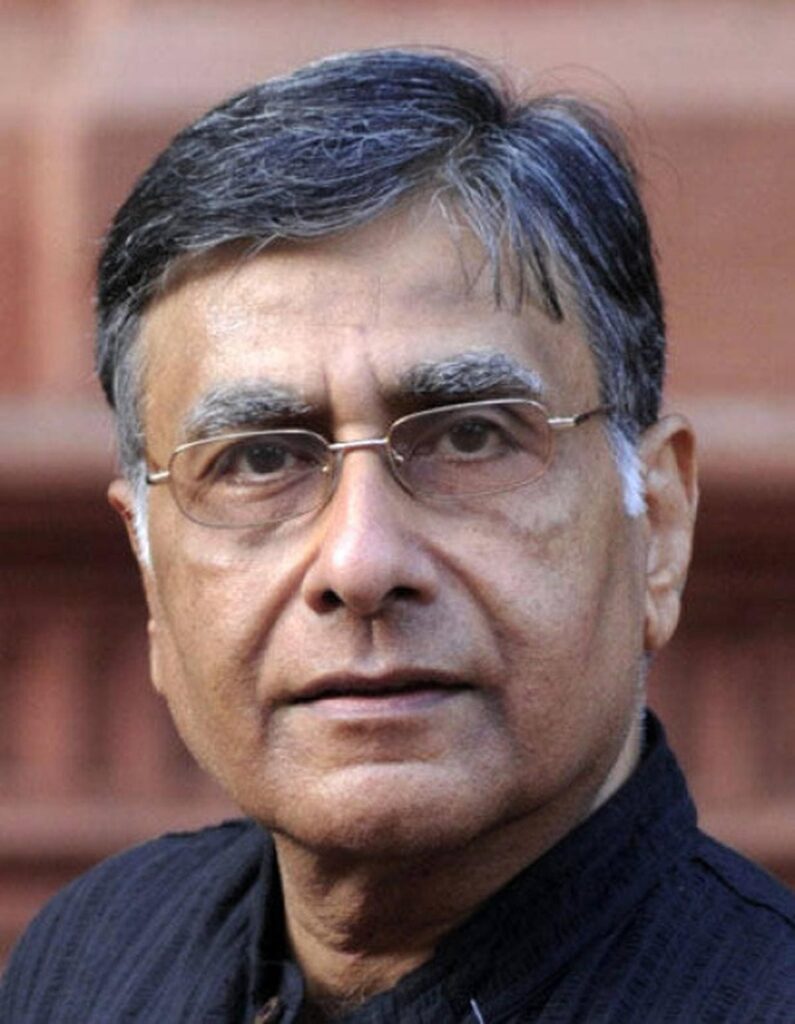

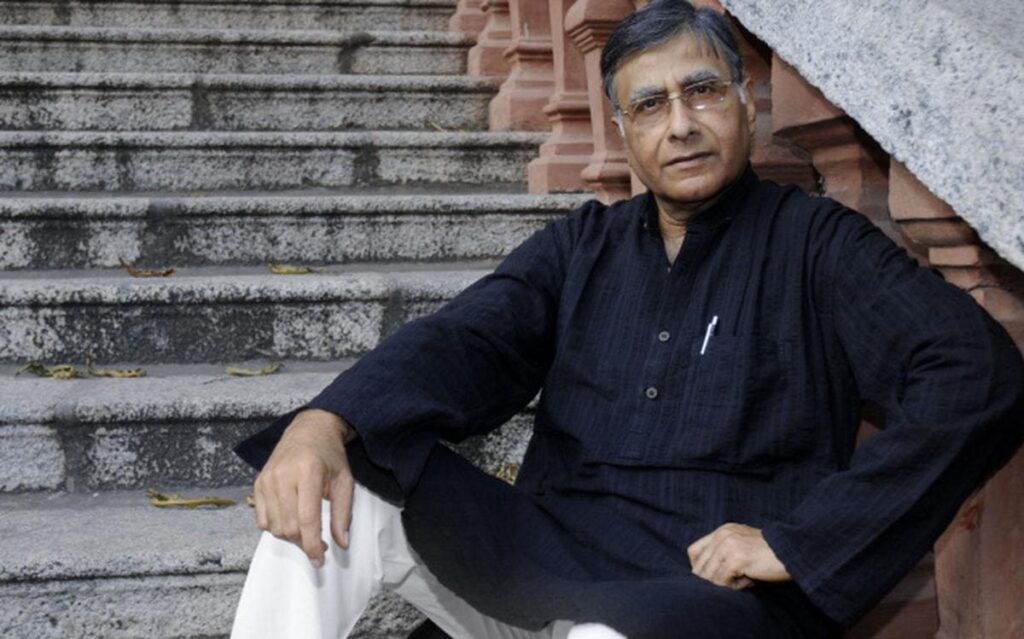

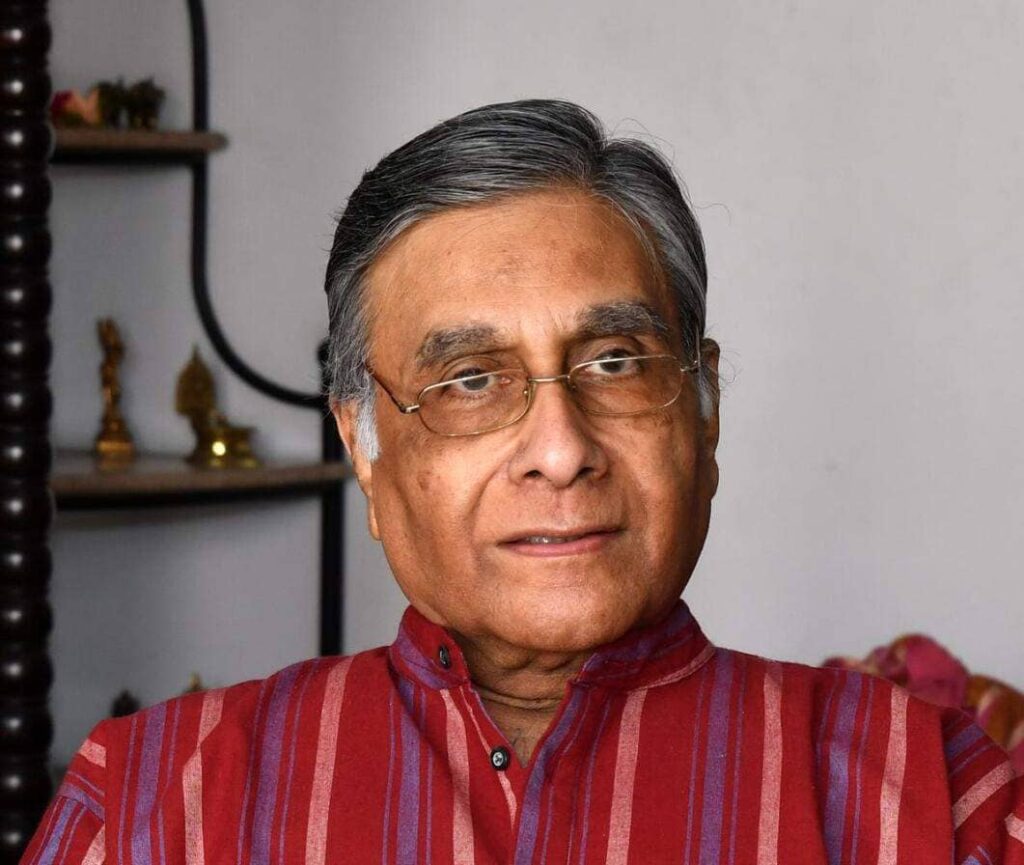

The Voice of the Matter

With over five decades of experience, P C Ramakrishna, Chennai-based voiceover artiste, theatre artiste, director, bass section singer in the Madras Youth Choir and pioneer English newscaster, walks us through his book, Find Your Voice. Breaking down voice into science and art, the book is a fascinating treasure trove of exercises to build and nurture the voice and is a reflection on the imperativenes of riyaaz in the context of the arts

Find Your Voice is a very powerful title on so many levels; did the title come first and then did you break down the book into its many chapters or did you write the book and then think of this title?

The voice has pretty much been the core of my being, one way or another, since I was a schoolboy. With fifty years plus as an actor with the Madras Players, I became more and more conscious of the human voice on stage. For most of these years, we acted in Museum Theatre (non air-conditioned till recent years), windows open, ancient fans making an unholy clatter, and Pantheon Road (Egmore, Chennai) traffic noises filtering through, without mics, and we trained ourselves to be heard clearly. Today’s young theatre actors seem to find it very difficult to be heard without amplification, even though Museum Theatre is now air-conditioned, and the fans relegated to the museum itself.

There are many capable actors who conduct acting workshops, but none, if any, who train the actor’s voice. To re-quote the great Laurence Olivier, “You may be the world’s greatest actor, but it is zilch if you cannot be heard”. It is to address this aspect of theatre that I started writing this book.

Again, I work parallely in the field of voiceovers, having to read scripts for documentaries, heritage films, and presentations ranging from the severely technical to medical and human interest. It is a rewarding profession which makes its own rigorous demands, perhaps why there are very few in the field. Young, and not so young aspirants have asked me over the years how to enter this profession. This book deals with the niche field of voice-overs. In fact, on request, I am conducting this month a two-day workshop for aspiring voice professionals.

This book has a section also on the singing voice. I sing bass with the Madras Youth choir, and I have shared the kind of rigour required for singers to express and retain their voice quality.

In sum, I would say that I wrote the book as it came, and the title suggested itself thereafter. You are right, the title goes beyond the demands of just the physical voice, but I wasn’t going to get into that!

In the context of the arts, finding your voice, aside from the literal sense of the word, is also very crucial, right? When did you actually find that voice? We don’t get to hear your personal story too much in the book.

As I have written briefly in my Introduction to the book, the French, Belgian and Irish priests in the school at Calcutta where I studied discovered this potential in me, even before I knew it. They recognised intuitively that I was more interested in the spoken word and the human voice than the next student, and created opportunities for me to hone my skill.

The work I do today to keep the home fires burning is entirely due to their foresight. More than twenty years after I left school, I discovered this profession, and thereby hangs a tale.

We love how you have treated voice both from the perspective of science and art; it is the coming together of both, right?

Yes. Voice is science plus art. That is why I have dealt with the physics of voice in the first chapter and the chemistry of it in another. However emotive and expressive one is, one can make no impression if the voice sounds like a bullfrog in the mating season.

Per contra, you can have a God-given voice, but if you have neither feel nor modulation, no one will listen to you. My take on this would be, a good voice is 40% voice quality and 60% feel.

In the chapter on The Chemistry of Voice, you talk about the classical school of acting where the “mind, instinct and the word direct action”. You turn to The Navarasas to elucidate the idea. Tell us a bit about your relationship with the classical arts and how it has shaped your thought, process and performance both as a theatre artiste and a voiceover artiste?

There are several schools of acting, as I have acknowledged in the book. The classical style in which I have been brought up works from the mind to the body, as I have detailed in the chapter on ‘Chemistry of Voice’. The Navarasas I have referred to apply to both dance and drama. It is the dramatic element of my training in theatre that has helped greatly in my voice-over work.

I have to reach an unseen audience ranging from corporate executives and technocrats to tourists and children. How I reach them through the modulation that makes sense to them is what I have drawn from my theatre experience.

The book is also a treasure trove of resources in terms of exercises, tips, strategies in terms of how to cultivate and nurture the voice. This is very generous of you; have you drawn from your own experiences or did you also have to research to write this book?

The chapter on exercises is largely from my own experience of what works, bolstered by the tips given by experts that bear out the work I do in this connection.

You also talk about the concept of rigour and riyaaz, taking us back to your days in Calcutta, watching maestros practice; why is rigour crucial and what is your own rigour?

Riyaaz is a must. Unless the actor or voice over artiste rigorously practises daily, the exercises laid out to maintain his or her voice are trim, sustainability is seriously compromised.